Posted on January 6, 2022 by Jena Lococo

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) signed into law last November infused $12 billion into carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology. Also tucked away in this monumental investment into CCUS was a small but mighty provision that has the potential to unlock a whole new wave of carbon storage projects.

The offshore environment has largely been untapped as a resource for the permanent storage of CO2, despite the vast storage potential. The lack of a comprehensive regulatory framework and arbitrary regulatory interpretations are partially to blame.

The Outer Continental Shelf Leasing Act (OCSLA) authorizes the Department of the Interior (DOI)’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to grant leases, easements, and rights-of-way for offshore energy development in federal waters. While not explicitly stated, DOI concluded they have the authority to permit the sequestration of CO2 for enhanced oil recovery on existing oil and gas leases and the geologic sequestration of CO2 for activities that “produce or support production, transportation, or transmission of energy from sources other than oil or gas.” BOEM interpreted this language to mean that only CO2 from coal-powered facilities (i.e., from sources other than oil and gas) could be captured and stored offshore. This interpretation effectively banned most types of offshore carbon storage projects.

The provision passed in Section 40307 of the IIJA now grants BOEM the authority to issue leases, easements, and rights-of-way in federal offshore waters for the sequestration of CO2, irrespective of the source of CO2. A CO2 molecule is a CO2 molecule, and it is essential that as many of them are captured as technically and economically feasible, regardless if they are captured from a power plant, an industrial manufacturing facility, or directly captured from the air.

The IIJA provision also clarified that offshore carbon sequestration would not trigger the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA), which was another obstacle to offshore storage deployment since it could have introduced duplicative permitting requirements.

Offshore carbon storage offers an attractive complement to onshore storage for a variety of reasons. It avoids heavily populated onshore areas – typically only one landowner is involved (e.g. DOI) – and there is reduced risk to underground sources of drinking water.

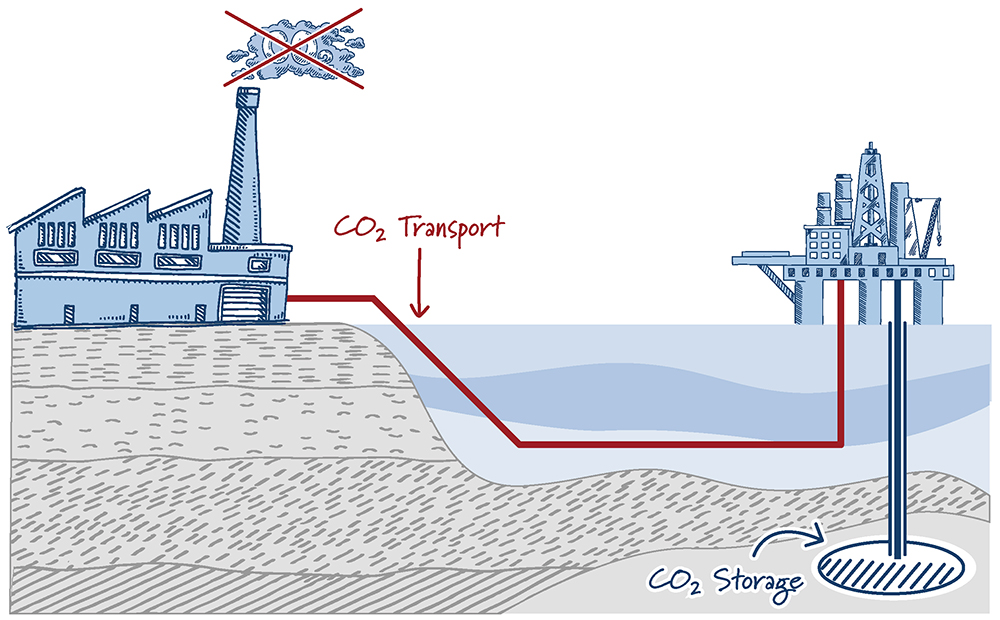

A Simple Diagram of Offshore Carbon Capture and Storage

For these reasons, momentum is building to sequester CO2 in the offshore environment, and more is expected with this new provision. Globally, investments and operations in offshore carbon storage are already happening, particularly in the North Sea. While no offshore carbon capture and storage project is currently in operation today in the United States, multiple projects are in the works:

The US Gulf Coast is a Promising Location for Offshore Storage

Despite a 2010 Interagency Work Group recommending that DOI and EPA begin to formalize coordination and develop regulatory frameworks for the offshore federal environment, the lack of a comprehensive regulatory framework for offshore carbon storage has long been recognized as an issue to jumpstart this industry. While these authorizations are a significant first step, many gaps still exist that DOI, in consultation with other federal agencies, will now need to address to establish a fit-for-purpose framework that will provide regulatory certainty to project developers and enable this industry to develop and thrive.