In 2017, hydropower generated more than four times as much clean electricity as solar. It consistently ranks as one of the cheapest and cleanest forms of energy.

According to the Department of Energy, America holds the technical potential to double the size of its hydropower fleet. More hydropower can be generated from small, environmentally-friendly projects and upgrades to existing dams. Yet, our hydropower potential is being held back by a cumbersome regulatory process and an uneven playing field.

Hydropower is well-established as a clean energy technology. In 2021, it held a 30% share of all renewable energy generation and a 6.1% share of total U.S. energy generation. While hydropower technologies continue to be developed and improved, inefficient permitting and outdated manufacturing hinder much of the deployment.

In 2023, there are three main types of hydropower plants: impoundment, diversion and pumped storage. As of 2021, there were over 90,000 dams in the U.S., of which less than 3% actually produce power.

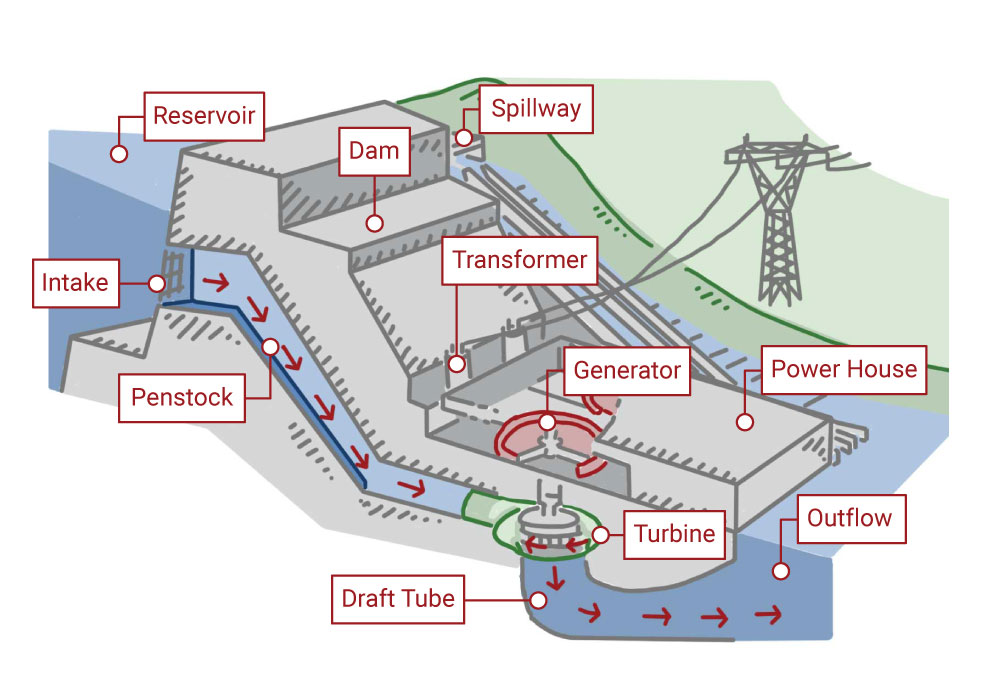

An impoundment plant uses a dam to create a controlled flow of water that spins a turbine to power a generator; they are the most common type of hydropower plant.

Impoundment Hydropower Plant

Source: DOE

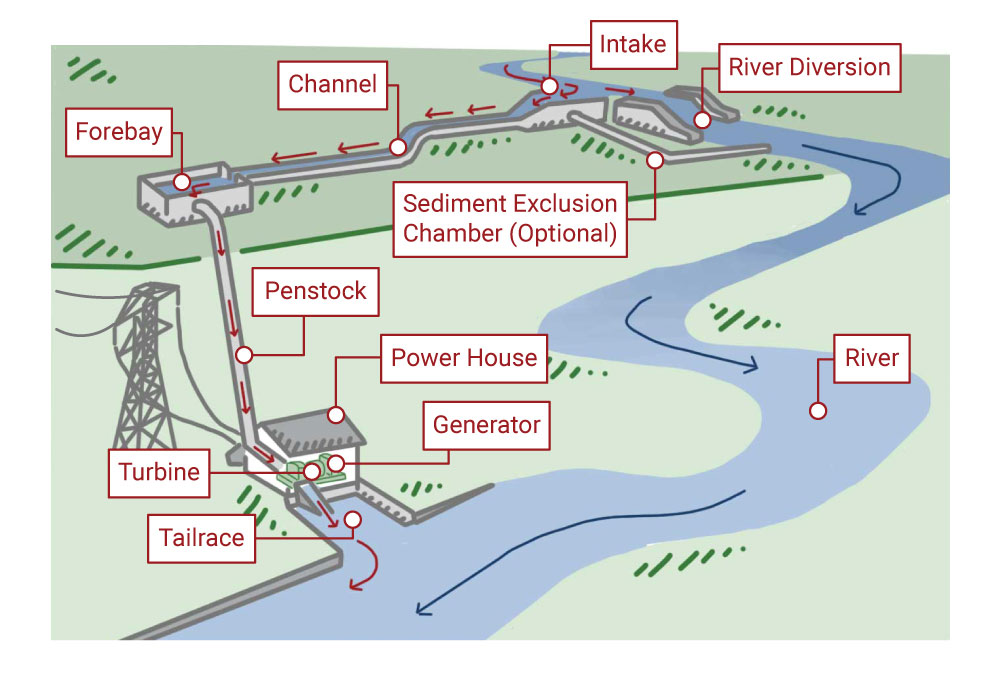

A diversion plant uses the natural flow of water to spin a turbine, which does not necessarily require a dam.

Diversion Hydropower Plant

Source: DOE

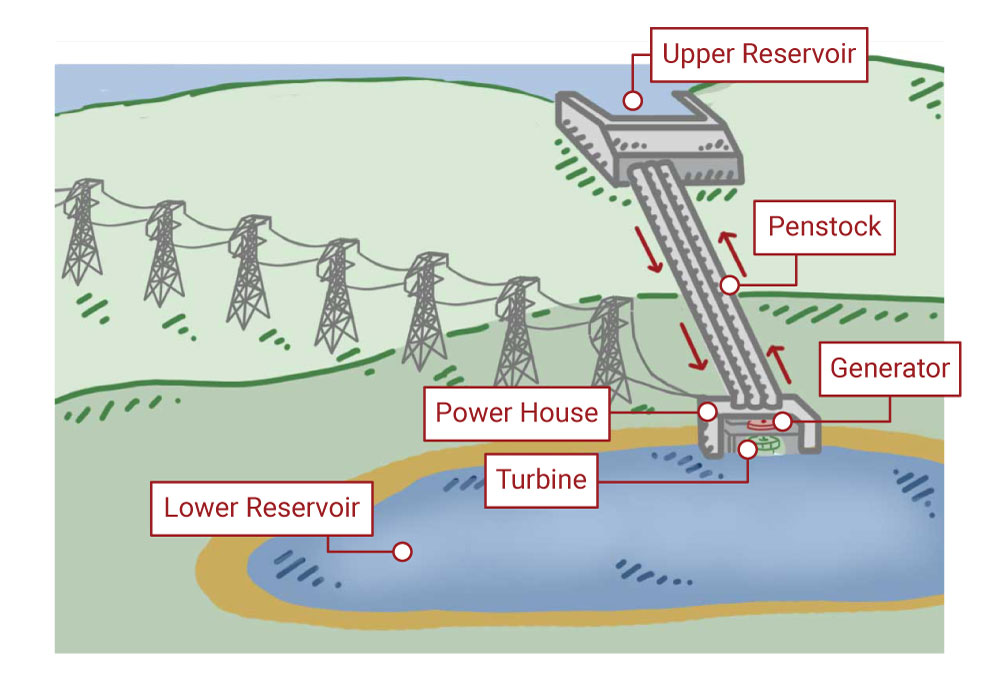

The third type of hydropower plant is a pumped storage plant. Pumped storage plants require two reservoirs, a lower and an upper. When electricity demand is low, the plant pumps water from the lower reservoir to the upper. When electricity is in high demand, the plant releases water from the upper reservoir back down to the lower. The natural flow of the water is able to make up for the increased demand. According to a 2023 report by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), “the U.S. currently has 43 [pumped storage hydro] plants and has the potential to add enough new PSH plants to more than double its current PSH capacity.”

Closed-Loop Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant

Source: DOE

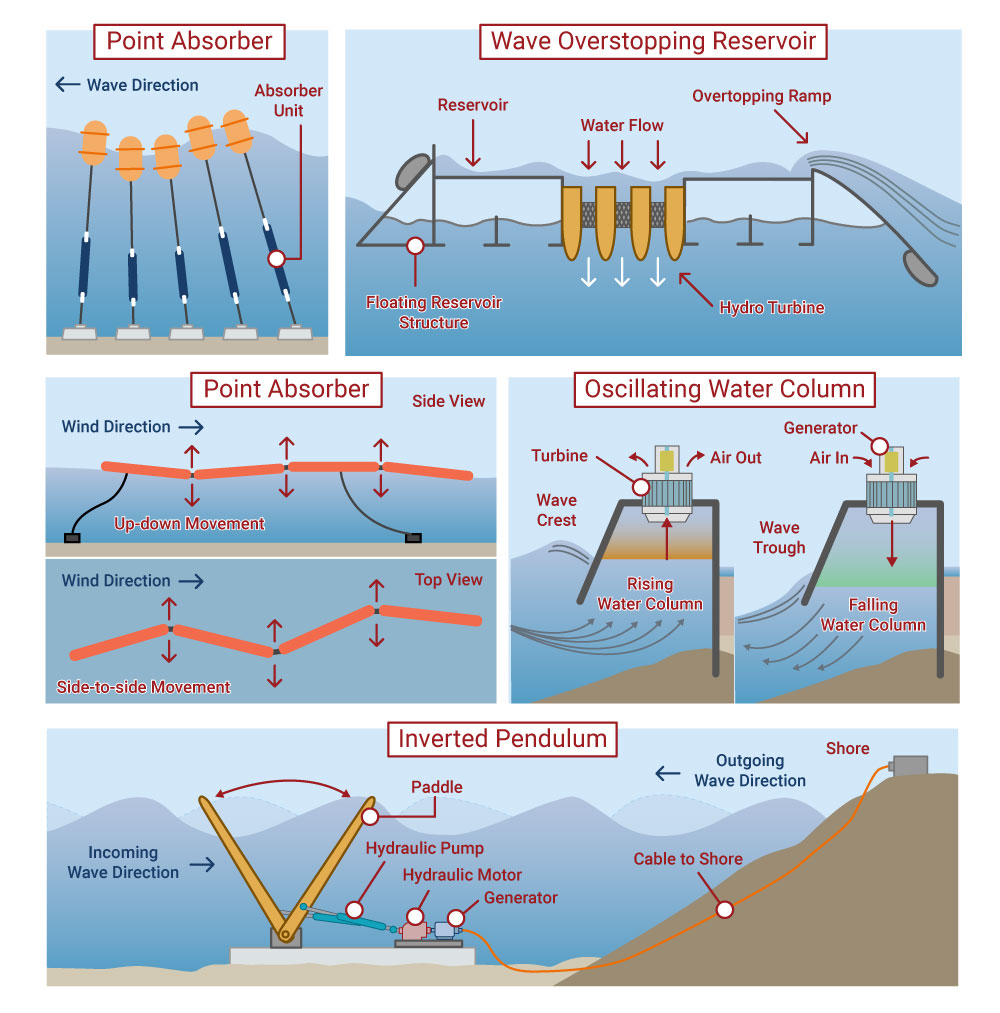

In addition to these types of plants, there is the lesser-known marine and hydrokinetic (MHK) energy technology. MHK energy uses the predictability of tidal movements to harness energy. As the ocean moves naturally, a variety of turbines and point absorbers can be used to generate electricity. Given that 70% of the earth is covered in water, MHK energy has plenty of potential. The greatest hindrance to MHK development is permitting. The permitting process for MHK can be even lengthier and more expensive than conventional hydropower because it not only features elements of traditional hydropower, regulated by FERC, but also must receive approvals from a host of impacted state agencies. While these technologies are promising, to access the full potential of our hydropower, policy must be reformed.

Various Types of MHK Technology

Source: DOE

Enable Electrification of Existing Non-Powered Dams Less than 3% of America’s 90,000 dams are outfitted with power generation equipment. These “non-powered dams” (NPDs) were built for other purposes, such as irrigation and flood control. Electrifying just the top 100 NPDs operated by the Army Corps of Engineers could generate electricity for over one million homes and create thousands of jobs, and ORNL estimates that electrifying these existing dams would boost America’s existing hydropower capacity by 15%, enough to power millions of United States homes.

Enable and Fund the Modernization of Existing Hydro Dams The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the largest generator of hydropower in the U.S. Hydropower plants owned by USACE make enough electricity to power 10 cities the size of Seattle every year, but the current hydropower fleet is aging. Most of these plants were built over 50 years ago, and between 2017 to 2019, only 30% of the total investment into hydropower refurbishment projects was designated for the federal fleet. As a result, privately owned plants continue to operate at higher average capacity factors (43%) than the federal fleet (36%). As upgrades have been deferred, the plants need more maintenance and suffer from increased downtime. New equipment would simultaneously maximize flows to federal coffers and bolster U.S. clean energy generation.

Streamline the Permitting and Regulatory Process Conversely, prospective hydropower developers may need to receive independent approval from over a dozen government agencies as the management of hydropower plants spans many government agencies. Hydropower developers must traverse a regulatory gauntlet: FERC, USACE, EPA, NOAA, FWS, NPS, BLM, USFS, SHPO, THPO and more. And that’s just at the federal level. State and local agencies may require additional paperwork.

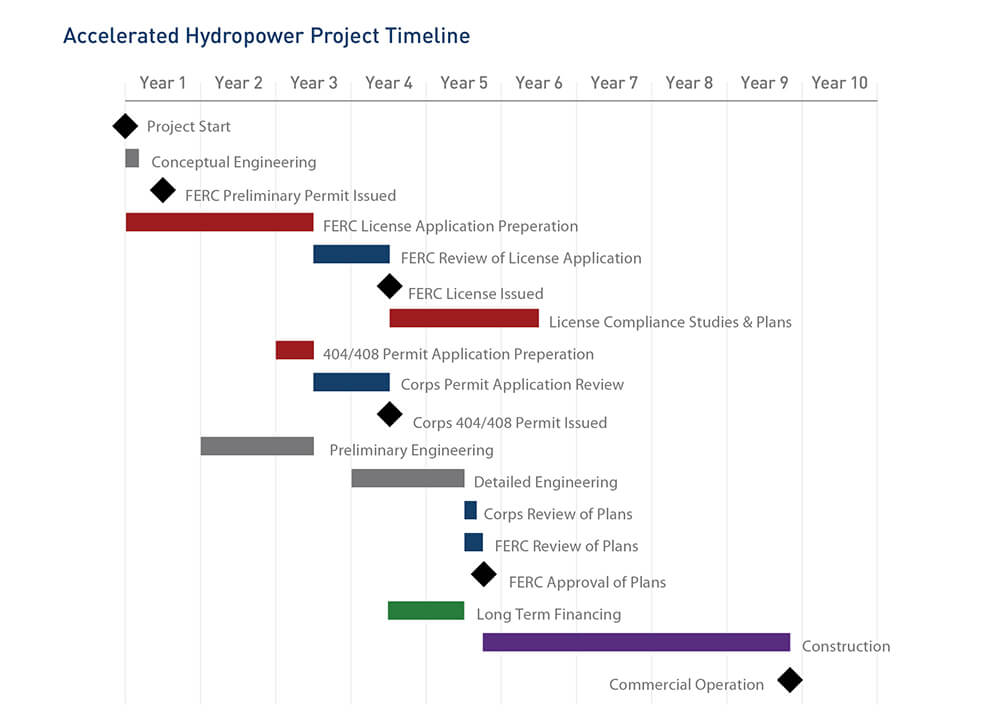

This predictably leads to slower permit times, high permitting costs, redundant requests, and inflated overall project costs. For example, one California plant required 38 separate studies with some costing more than $1 million each. Relicensing a single plant has the potential to cost over $50 million dollars and in some cases, delays force the process to take over 17 years. In the case of a Maryland-based company, regulatory compliance comprised more than 25 percent of the total project cost. Even in an ‘accelerated’ schedule, it still takes about 10 years to complete a hydropower project. At the end of 2021, out of the 1,744 MW worth of hydropower projects that were in the deployment process, less than 6.2% (108 MW worth) were under construction, while the rest were stuck in various stages of licensing. Moreover, most of the projects fell into the preliminary permitting category. Opportunities exist to streamline this process without compromising the environmental permitting process.

Example of an accelerated development schedule for a hydropower project licensed under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Source: Department of Energy’s Hydrovision Report, Ch 2: State of Hydropower in the United States

Allow Hydropower to Qualify as Renewable Resource for Federal Procurement Finally, the federal government is required to purchase 7.5% of its energy from renewable sources, pursuant to the Energy Policy Act of 2005. While ideally this requirement would recognize all clean energy, not even existing hydropower is recognized as renewable under the purchasing requirement. Allowing existing, underutilized hydropower capacity to qualify could reduce federal spending while preserving the government’s commitment to clean energy.

Source: Emrgy