Posted on June 20, 2024 by Kelsey Grant and Savita Bowman

One of the most exciting clean energy technologies the United States leads the world on is carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). The world’s abundant natural resources, or using them for industrial activity don’t alone create climate change, the emissions from them do.

That’s why reducing carbon dioxide emissions at scale doesn’t mean you must scrap existing technology. In America, we have the incredible ability to innovate our way to a clean energy future. CCUS can be used in the power sector to reduce emissions from natural gas and coal fired generation, ethanol production facilities, and difficult to decarbonize industries such as steel and concrete.

Perhaps you’ve heard that CCUS is expensive, or that it’s only going to benefit the oil and gas industry. At ClearPath, we follow the facts, so let’s dig into how this technology is cross-cutting and how it can be an economically viable tool for lowering global emissions.

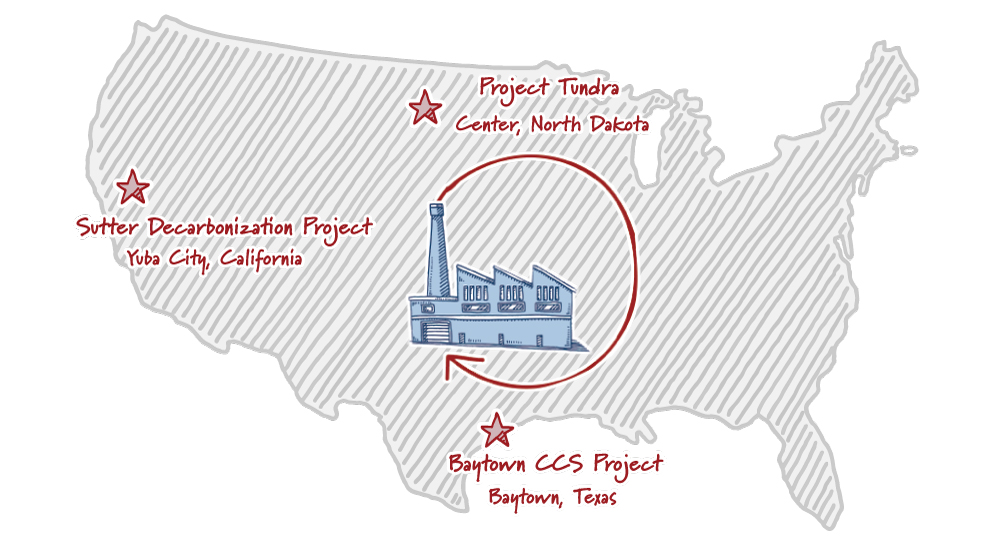

Congress authorized a moonshot program in the Energy Act of 2020 to create a federal demonstration program to work with private sector innovators to scale up new technology. In 2021, Congress funded the program through the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). In December 2023, the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) selected three carbon capture demonstration projects for award negotiations, totaling $890 million in potential awards. These projects include the Baytown CCS Project in Texas, Project Tundra in North Dakota, and the Sutter Decarbonization Project in California.

Energy innovation is a little different than, say, a new app for your phone that runs algorithms. These are large construction projects that require millions of dollars of capital to build — just to see if the technology can work in real-world settings. The U.S. has a proud history of supporting energy projects in the early stages of development using demonstration programs. Once new technology is proven and shows its ability to lower commercialization costs, the private sector can adopt the technology. You can call this a public private partnership, or you can call it American innovation leadership coupled with good old-fashioned, market-based principles.

OCED is a critical piece of this innovation pipeline to aid in the transition of ideas from a lab to real-world applications. OCED’s CCUS demonstration projects can spur additional private-sector investment, and support the development of critical transportation and storage infrastructure across the CCUS supply chain.

Recognizing the importance of CCUS technologies in the Energy Act of 2020, Congress followed it up with the bipartisan IIJA of 2021, which allocated DOE $12 billion to carry out a range of carbon management initiatives, from direct air capture hubs to a CCUS demonstration program. IIJA also established OCED to help administer these new initiatives in collaboration with the private sector.

3 awarded, 3 more to go

The Energy Act and IIJA authorized and funded six potential CCUS demonstration projects. So far, only the three projects we mentioned have been selected for award negotiation – and none have officially received any award funds yet. A timely and efficient rollout of these critical funding opportunities will provide applicants visibility into expected timelines and decision-making milestones and ensure this program has the impact Congress intended.

Coordination of federal programs

A full value chain approach is critical for effectively demonstrating and deploying carbon capture technology. That includes developing a dedicated, diverse and reliable carbon transportation network, including pipeline, truck, barge, rail, and storage infrastructure.

To do this, OCED can leverage funding opportunities from other DOE programs, because once you capture the carbon it needs to go somewhere for utilization or storage. For example, Project Tundra, selected for award negotiation in the carbon capture demonstration program, has participated in DOE’s CarbonSAFE Initiative, which supports carbon storage projects. Another example is the DOE Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance (CIFIA) program, which provides loans and grants to carbon transport project developers. By ensuring all midstream partners involved with OCED, from private sector pipeline to barge operators, are aware of and eligible for CIFIA support, funding opportunities can be leveraged across programs to support this critical transportation infrastructure. As DOE facilitates connections across complementary programs, it will be important that selected projects are co-located with other CCUS hubs and infrastructure to minimize duplicative efforts and optimize federal resources.

DOE could also facilitate the sharing of key learnings with CCUS demonstration program participants, including midstream and downstream project partners, and other offices. For example, in December 2023, DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (FECM) announced $40 million in funding for technical and informational educational assistance for carbon transport and storage project developers. DOE could ensure any learnings and best practices identified through FECM programs are transferred to participants in OCED’s carbon capture demonstration program and project partners. In addition, OCED can also provide specialized support for these demonstration projects. DOE can help applicants identify strategies to reduce project costs, hire personnel with the necessary skills and expertise, manage stakeholder relationships, and create plans to manage these large, complex projects.

Don’t forget about permitting

The timeline for permitting these projects is currently a tremendous barrier to success. Cross-agency coordination will be key to ensuring administrative delays do not prevent the build-out of transportation and storage infrastructure and hinder applicants’ ability to secure funding opportunities. Each part of the CCUS value chain is subject to its own unique, complex regulatory requirements that could fall under state or federal jurisdiction depending on the state. For example, applicants to DOE’s carbon capture demonstration program are required to obtain a Class VI permit, which allows for the underground storage of carbon. These permits are regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or, in some cases, by states that have been given authority, also called primacy. DOE requires applicants to provide evidence that these permits have been obtained or submitted to the EPA. If an applicant does not have a permit, they must explain when they expect to receive it.

However, the timeline for obtaining Class VI permits from the EPA can be long and unpredictable. It can take the EPA six years to issue a Class VI permit, and the agency has been slow to grant primacy to states – which have proven their ability to grant Class VI permits in a fraction of the time. A couple of perfect examples of how Class VI primacy works wonders are North Dakota where the state was able to issue a permit for Red Trail Energy in less than five months, or in Wyoming where their Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issued a draft permit for Tallgrass Energy’s Juniper I-1 well in just over one year.

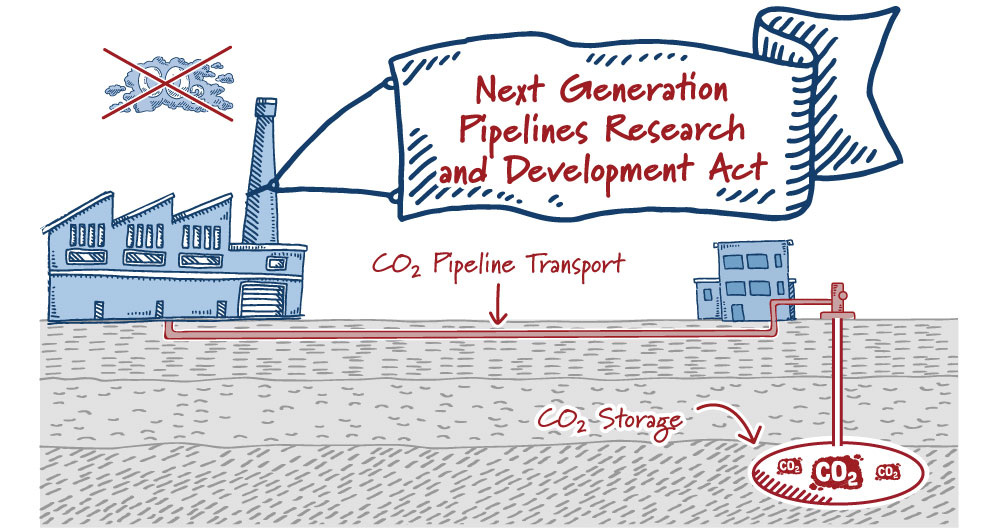

Similarly, applicants must also demonstrate they will have access to transportation infrastructure. However, carbon pipelines, which are regulated at the state level, have encountered an unpredictable regulatory environment, leading to significant delays and even the cancellation of projects. Streamlined permitting for carbon pipelines and updated Congressional direction for carbon pipelines R&D and safety standards would aid in the build-out of this key infrastructure.

Congress is already leaning into the issue of improvements to pipeline permitting and development. In March of 2024, the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee passed the Next Generation Pipelines Research and Development Act with bipartisan support. This bill would seek to modernize our pipeline system by authorizing new research and development programs focused on various pipeline technologies and uses, including the transportation of carbon.

From R&D, demonstrations, and transport we covered here to the private sector incentives known as 45Q, Congress has put the pieces on the table to finally scale up carbon capture. If we can find the proper permitting piece, and put them all together, the United States can reduce emissions at home and turn the innovations and technologies into business opportunities for American developers to find customers all around the world.