Posted on September 18, 2025 by Jake Kincer and Nick Lombardo

American innovation drives energy security, a key factor in geopolitical influence. The U.S. can leverage its energy abundance by putting energy at the center of its foreign policy strategy, mutually benefiting America’s partners while reducing global emissions and advancing U.S. national interests. As Secretary of State Marco Rubio made clear, energy will be “at the forefront of foreign policy for the next 100 years.” To meet this moment, the U.S. must lean into its strengths and create a coordinated, agile and effective energy diplomacy and delivery system.

One way to do so would be through the bipartisan creation of Energy Security Compacts (ESCs) that align American technical assistance and financing tools to strengthen the Trump Administration’s work in elevating energy security as a core pillar of U.S. foreign policy.

The American foreign policy apparatus has become enormously cluttered. Institutions from the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) to the Export-Import Bank of the U.S. (EXIM) work hard for the American people, but disjointedly toward scattered goals.

On the other hand, American adversaries are speeding ahead. The Chinese Belt and Road initiative, led by state-backed or outright-owned corporations, deploys large amounts of capital in a coordinated effort. In Brazil, for instance, the largest Latin American economy, China has invested more than $60 billion into the nation’s energy sector since 2015. The Chinese Communist Party now controls over 12 percent of Brazil’s energy infrastructure. Meanwhile, the U.S. government’s foreign investment institutions have supported less than $472 million, with one of the main projects being a streetlighting system. Worthwhile, but not transformative or strategic.

While trying to out-subsidize China is unrealistic and economically unsound, the U.S. needs to leverage its strengths. Countries want to work with the American private sector, which is the largest and most innovative in the world, but U.S. companies are at a disadvantage. For example, Egypt wanted to select American nuclear technology for its El Dabaa power plant, but ultimately had to go with Russian technology. America is the preferred vendor for many countries, including Ghana, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia, but private businesses can’t compete alone against heavily state-subsidized corporations. U.S. policies should level the playing field to support U.S. business and streamline bureaucracy so we can more effectively use the tools we do have.

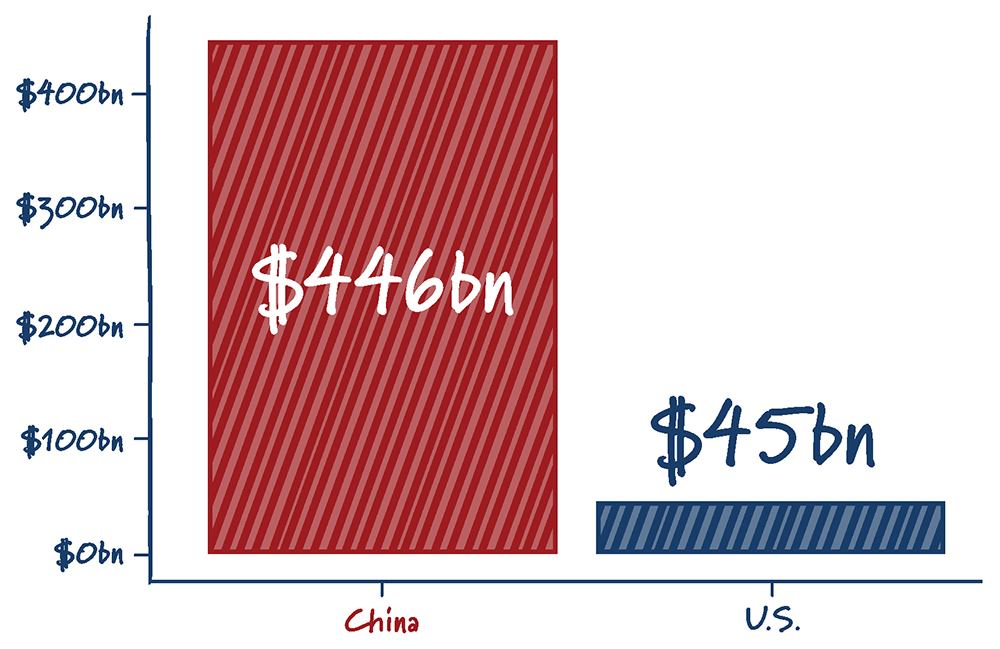

Chinese energy finance from official sources is 10x more than the U.S. since 2015

The creation of the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and the modernization of EXIM under the first Trump Administration were strong steps towards a more proactive international policy. While those tools need to be sharpened further through their upcoming reauthorizations, the next step toward ensuring American energy dominance and global prosperity is to build an Energy Security Compacts mechanism to maximize the toolkit’s effectiveness.

America already has a model to build on. The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) utilizes a compact framework that can serve as a platform to coordinate the interagency, advance American national security interests and support American energy innovations in foreign markets. These compacts would be bilateral, U.S.-led engagements designed to:

Imagine how this might work in a country like Brazil, a nation with vast reserves of rare earths that the U.S. needs for advanced manufacturing, energy and defense, but whose power grid is unreliable and vulnerable to droughts. An ESC would begin with a joint analysis of the country’s energy and infrastructure bottlenecks and result in a five to 10-year framework that channels existing U.S. tools toward projects that both strengthen Brazil’s grid and directly advance U.S. strategic and economic interests.

This ESC would align American technical assistance and financing tools, some of which already operate on a cost-recovery basis and often return money to the U.S. Treasury. This could be designed to support a portfolio of complementary projects to build out mining capacity in commodities the U.S. needs and the energy infrastructure to support those projects and provide reliable power to Brazil’s interior. The USTDA could fund feasibility studies and early engineering work across the projects, while MCC provides grant capital for new transmission lines and capacity upgrades. The DFC could take equity stakes in new mining facilities, as it did with TechMet, supplied by EXIM-financed power plants built with American components, like in the Bahamas or Honduras. With the right alignment, these tools could offer more than fragmented assistance; they could deliver a unified, strategic alternative to America’s adversaries that reflects the full strength of U.S. innovation, partnership and purpose.

By combining diplomatic leadership from the U.S. State Department, commercial support from the Commerce Department and technical expertise from DOE, and the financing muscle from DFC and EXIM, an ESC with Brazil would help the U.S. compete more effectively with China. Therefore, strengthening critical supply chains in a fiscally responsible way. In short, this is a smart investment in American national interests, not just aid for Brazil.

Congress has an opportunity to work with the Administration to make this kind of scenario a reality, successfully replicated with America’s strategic partners and allies. Instead of reacting to Chinese and Russian efforts to corner global energy markets, U.S. efforts can proactively empower the private sector to unlock economic opportunity and advance our national interests for mutual benefit with our partners abroad. ESCs can be a bipartisan next step to build on America’s aim to lead the world in deploying affordable, reliable and clean energy systems, while recognizing the central role of energy security to geopolitical influence and reducing global emissions.