Posted on April 13, 2023 by Jonika Rathi and Spencer Nelson

Federal and private sector investments have unlocked exciting carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) development opportunities. Projects like the Lone Cypress Hydrogen Project in California, or the Air Products Clean Energy Complex in Louisiana plan to make hydrogen from natural gas while sequestering the carbon dioxide (CO2). Another project like the Navigator CO2 pipeline has the potential to deliver 15 million metric tons (MMT) per year of captured CO2 from ethanol facilities in five Midwestern states.

Carbon capture projects like these need a full chain of infrastructure from capture to transportation and storage — in the absence of a streamlined regulatory system, technology adoption will hit major roadblocks. Today, we have a two-fold challenge — educating all stakeholders on the impeccable safety record of sequestering carbon dioxide; and how we can modernize permitting to meet the scale and speed of development needed for clean energy goals.

Recent policy has bolstered support for CCUS technologies, incentivizing significant commercial investment into new projects. The bipartisan Energy Act of 2020 authorized $3 billion in funding for carbon capture pilots and demonstrations to be funded by the Department of Energy (DOE). These programs were later appropriated by the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), along with $3.5 billion in funding for four direct air capture hubs. Additionally, in 2022 the federal 45Q tax credit was both expanded and extended for six more years, as shown to the right:

The number of CCUS projects announced since 2018 has increased exponentially, with a total carbon capture capacity of over 118 MMT CO2/year planned by 2030. Despite these announced projects, the infrastructure to transport and permanently store the captured carbon is still nascent.

There are a variety of ways to both transport and securely store CO2. Trucks, trains and ships can be used for transporting small quantities of CO2, while pipelines are the most efficient for transporting large quantities over long distances. For storage, sequestration in deep saline aquifers is the most mature method. Another method being, permanent storage in a solid form in reactive rocks such as basalt through mineralization.

Many sources of CO2 are at considerable distances from suitable storage sites. In order to facilitate the effective deployment of carbon capture on a large scale, we need to ensure regional pipeline networks exist throughout the country along with branch lines (or spurs) connecting individual sources. The U.S.’ existing network of more than 5,300 miles of carbon pipelines connects less than 40% of the states.

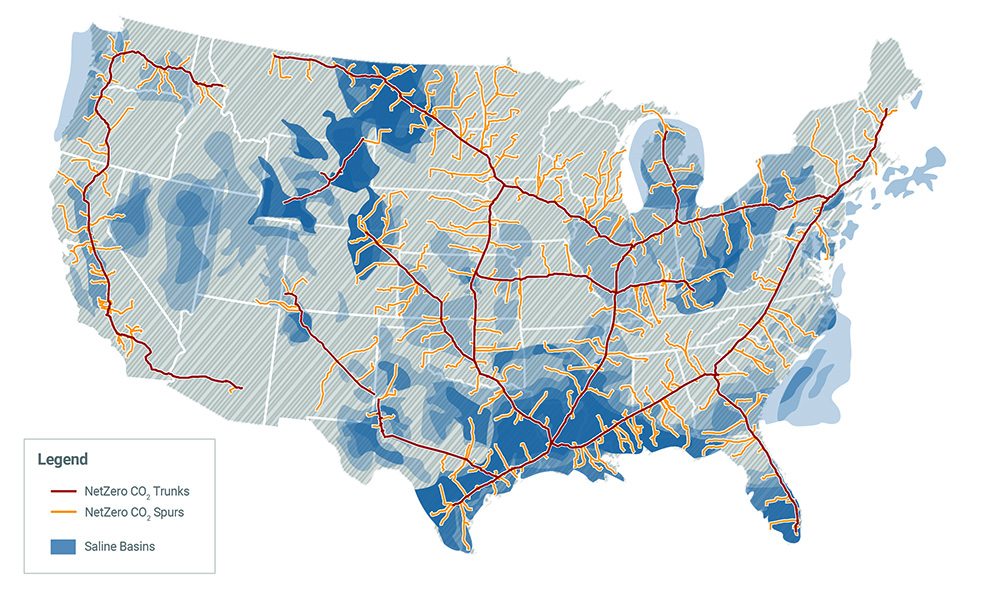

Many net-zero modeling analyses projected that the required annual storage rates could reach over 1 gigaton (Gt) of CO2 by 2050 to achieve net-zero goals through a high electrification scenario. At that rate of carbon storage, we would need a CO2 pipeline system stretching over 65,000 miles, 13 times larger than the current pipeline system. If developed, this network could cover the majority of the high-capacity storage saline basins, extensively increasing access to both onshore and offshore CO2 storage. Other modeling scenarios with a higher proportion of CCUS technology deployment might result in an even more extensive network.

An illustration of a pipeline network on a gigaton scale is shown below. ClearPath estimates that we would need a minimum of 650 Class VI wells by 2050 to accomplish the carbon storage levels mentioned in the above scenario, compared to only three in operation today.

Illustrative 2050 Net-Zero CO2 Pipeline Network

Sources include ClearPath analysis, National Carbon Sequestration Database Saline basins, and Princeton’s Net-Zero America spur and trunk line transmission expansions for the high-electrification scenario.

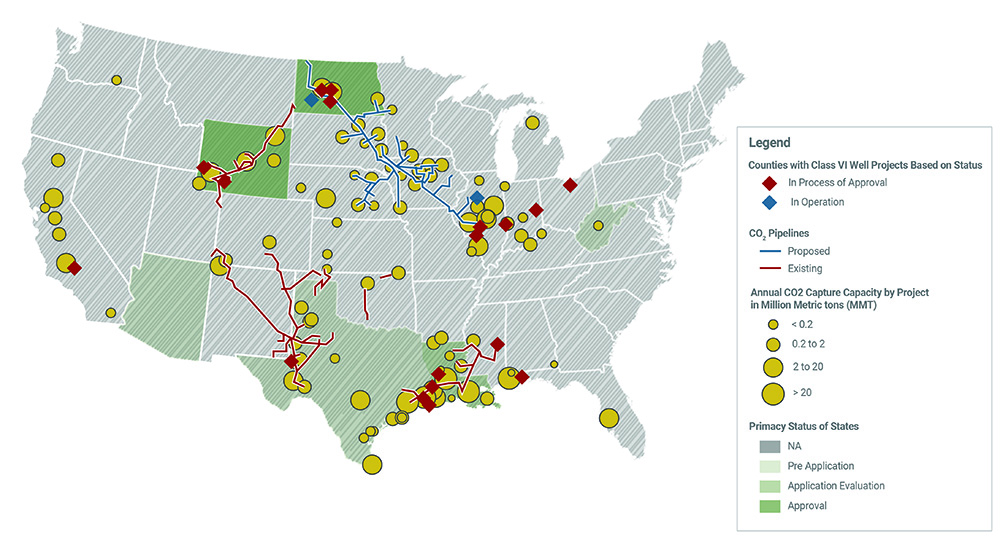

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates the safety and storage of CO2 underground using “Class VI wells”. So far, EPA’s approval of individual Class VI wells has been a slow and complicated process, with only two approved injection wells, both located at Archer Daniel Midland’s ethanol plant in Macon County, Illinois.

States are eligible to run the Class VI program themselves (also known as “primacy”) if they can demonstrate the capacity to approve and regulate under EPA guidelines. North Dakota and Wyoming currently have primacy over Class VI wells, and four additional states – Louisiana, Texas, Arizona, and West Virginia – are in the primacy application process. With only two EPA-approved wells and one state-approved well, the Red Trail Energy’s ethanol plant in North Dakota, currently in operation, there is mounting pressure from potential CCUS hub developers to expand CO2 storage capacity.

EPA is currently reviewing applications from 69 Class VI wells, each of which EPA estimates to have a three year timeline. In contrast, the North Dakota permit issued last year was granted within 9 months.

A recent report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates announced projects representing 97 MMT CO2 of annual storage capacity across 55 CCUS projects, meaning about 100 more Class VI wells are likely needed by 2030. However, all of this combined is only one-tenth of the scale needed for a net-zero energy system.

The figure below shows the current state of play for CCUS projects in development, carbon pipelines currently in operation or publicly announced, as well as counties with individual Class VI well applications that have been accepted for review by either the EPA or state governments.

Current and Proposed U.S. Carbon Capture Infrastructure

Sources include ClearPath analysis, CATF US Carbon Capture Map, Rextag CO2 Pipelines, and EPA’s Class VI Well Tables as of March 2023

When you compare the current and proposed pipeline network with the first map, it’s evident that we need to improve our pipeline development rate. The first step to building such an expansive transport network is a clear and efficient permitting process.

In order to seize the carbon capture and removal opportunity, there are a few policy actions that could help:

Projects like Lone Cypress and Air Products do not have the transportation and storage networks that are required to sequester CO2 yet today, and other projects like the Navigator pipeline will benefit from additional regulatory clarity. Agencies need to act now for us to meet our clean energy goals.