Posted on September 30, 2021 by Spencer Nelson

We need more clean energy technologies that can be ramped up affordably. And while some in Congress are pushing costly climate plans, we want a cleaner environment done the right way: with more innovation, not burdensome regulation or taxation. Despite the partisanship we are seeing today, Congress thankfully passed one of the biggest advancements in clean energy and climate policy in over a decade – the monumental Energy Act of 2020.

Tucked away in the 5,000 page end of 2020 omnibus was a wholly bipartisan, clean energy innovation roadmap.

Research, development and demonstration (RD&D) programs can have a tremendous benefit in reducing early stage technical risk for new technologies. This is particularly the case in the energy sector, where projects can be capital intensive and competition is fierce. The Department of Energy (DOE) has been a leader in accelerating the development of new technologies by investing in the development of breakthroughs like hydraulic fracturing, nuclear energy, solar and much more. The Energy Act of 2020, once implemented, has the potential to spur significant economic development, emissions reductions, and cost savings in the energy sector, largely through R&D and reduced taxes. Programs included in the Energy Act are expected to cumulatively reduce between 1,400 and 2,500 million metric tons of CO2 over the next 17 years. That’s why we call the Energy Act of 2020, signed by President Trump, the biggest climate bill in more than a decade.

The Energy Act was spearheaded by then-Chairman Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Ranking Member Joe Manchin (D-WV) of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Chairman Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) and Ranking Member Frank Lucas (R-OK) of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, as well as Chairman Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and then-Ranking Member Greg Walden (R-OR) of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. It represents dozens of individual bills from many Members of both parties in both the House and Senate, and represents the hard work of multiple months of comprehensive negotiations between both sides of the three committees.

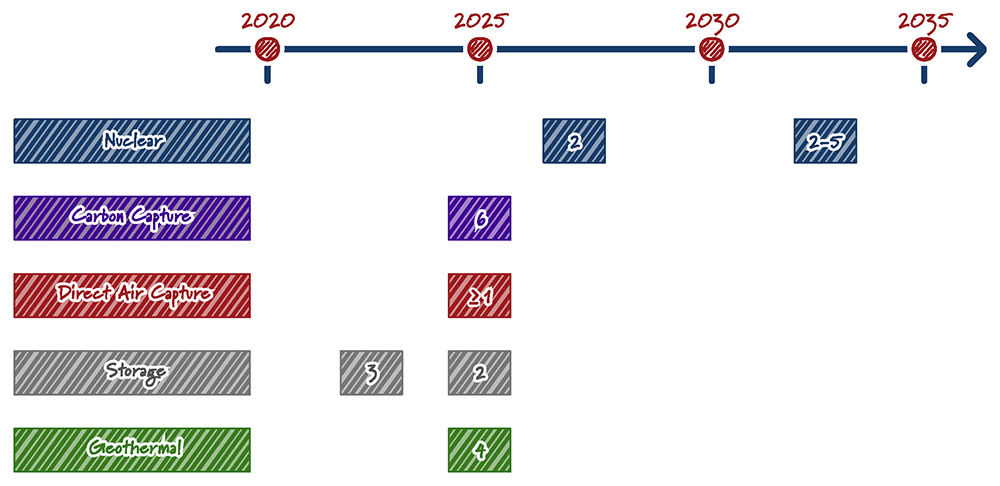

It modernizes and refocuses the DOE’s research and development programs on the most pressing technology challenges — scaling up clean energy technologies like advanced nuclear, long-duration energy storage, carbon capture, and enhanced geothermal. Crucially, across all of these technologies, DOE is now empowered to launch the most aggressive commercial scale technology demonstration program in U.S. history. The law ultimately establishes a moonshot of more than 20 full commercial scale demos by the mid-2020s.

Energy Act Commercial Demonstrations

In addition to these large five specific rewrites of policy, it contains significant reauthorizations for solar and wind, critical minerals, grid modernization, the DOE’s Office of Technology Transitions, and ARPA-E. Outside of DOE, the law included important tax credit extensions, for clean energy technologies like carbon capture and new offshore wind. One of the largest climate provisions authorizes regulations to phase out a greenhouse gas called hydrofluorocarbon in a cost effective and predictable manner.

Of course, the real impact of the Energy Act will only be realized once it is fully funded and implemented by appropriations. Once that happens, the impact is expected to be significant. Much of the funding required to implement the Energy Act is included in the bipartisan infrastructure bill pending before Congress.

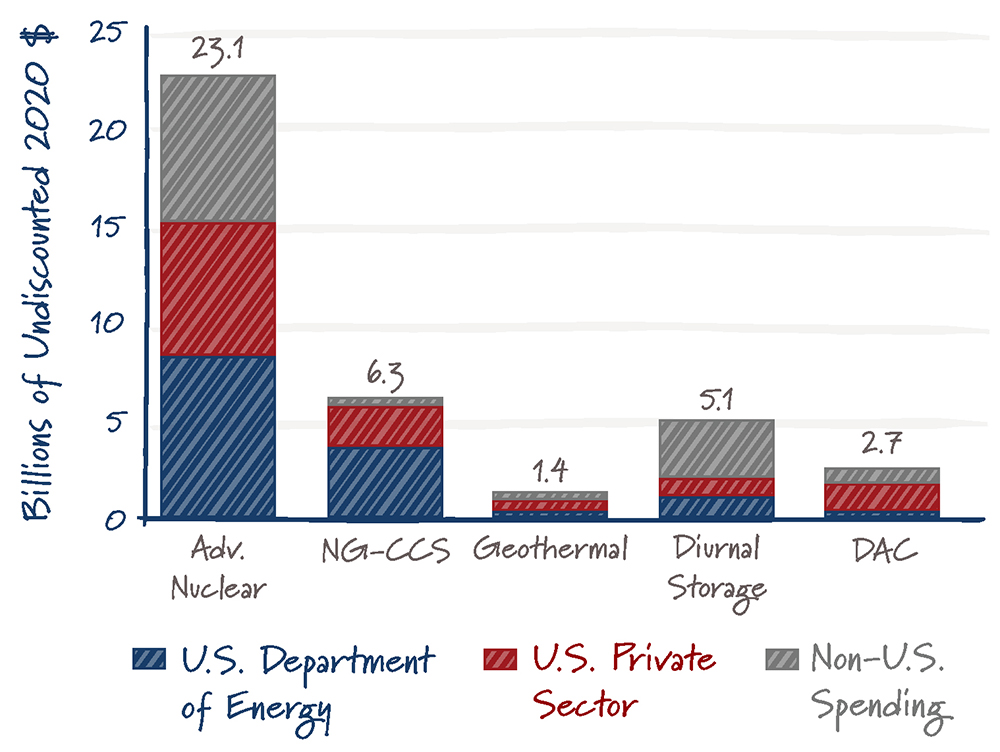

The think tank Resources for the Future (RFF) recently published an analysis of the impact of the Energy Act for five advanced energy technologies if fully funded for 10 years. They interviewed 26 experts on the impacts of the Energy Act programs for advanced nuclear, energy storage, natural gas carbon capture, direct air capture, and geothermal technologies. They found that even for just these five technologies, the total benefit outweighs the cost of the federal funding, with the average societal benefit of EACH technology program to be $30 billion.

The benefits of investing in these clean energy research programs range from economic growth, reduced carbon emissions, reduced air pollution, and reduced electricity cost. RFF found that federal investment in these technologies would lead to significant follow-on R&D investment from the private sector as well as international support for these technologies.

Projected Effect of Legislation on RD&D Spending If Fully Funded for 10 Years, FY 2022– FY2031

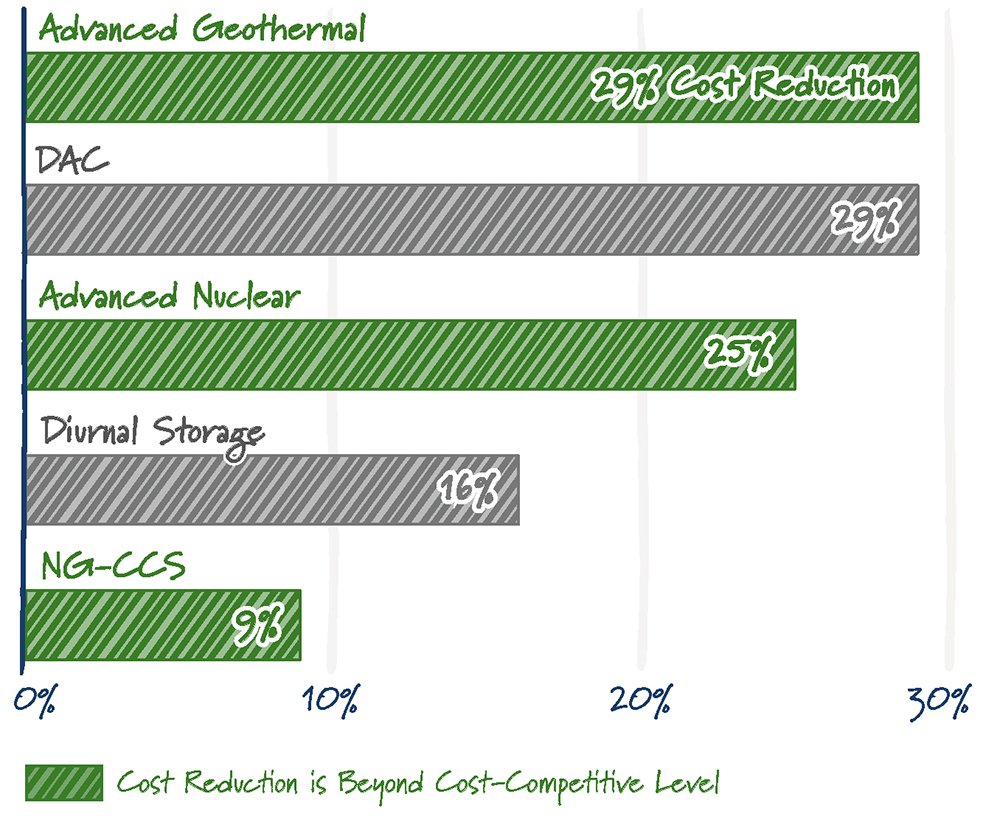

RFF also found that the Energy Act funding would significantly reduce costs so the technologies can move from an uncompetitive cost to a competitive cost.

Estimated Average Cost Reductions in 2035 Due to 10-Year RD&D Funding

Developing cheaper clean energy technologies benefits emissions reductions as well. RFF found that 10 years of funding at the Energy Act levels for these technologies would reap significant emissions reductions over the next 17 years. They found that the total emissions reductions from these policies would represent between 142 to 1,029 million metric tons of cumulative CO2 abatement through 2038. Total deployment of these advanced energy technologies would range from 25 to 75 gigawatts of capacity.

Elsewhere in the Energy Act of 2020 were other significant bipartisan emissions reduction policies. The law included a two-year extension for the 45Q carbon capture tax credit, which provides $35 per metric ton of carbon dioxide utilized in products or enhanced oil recovery, or $50 per ton of CO2 sequestered. The two-year extension in the Appropriations Act allows any project that commences construction by the end of 2025 to qualify, giving developers enough time to utilize the credit. This two-year extension of 45Q is expected to single-handedly result in an additional 53 to 113 million tons of capture capacity, which corresponds to an additional 342 million to 585 million tons of avoided carbon emissions over the next 15 years.

Another major climate policy passed in the 2021 Appropriations Act is a phaseout of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), common refrigerants that contribute heavily to climate change. Analysts have estimated that this policy will reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the United States by 900 million metric tons of CO2e over the next 15 years, which is more than an entire year of carbon emissions from Germany.

In total, this means just these portions of the Energy Act — the five advanced energy R&D programs, the 45Q tax credit, and the phaseout of HFCs — could collectively represent a reduction in carbon emissions of between 1,400 and 2,500 million metric tons of CO2e over the next 17 years all while reducing energy costs and creating economic growth. The full benefit of the law is likely much higher.