Posted on June 28, 2023 by Jasmine Yu

The ocean is a promising tool for carbon dioxide removal (CDR). It covers over 70% of the surface area of the planet, holds about 50 times more carbon than the atmosphere, and can store carbon for millennia at its deepest depths. The ocean removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through two main ways: 1) a natural chemical adjustment system: where the seawater absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and 2) by photosynthesis of organisms, like seaweed, to remove carbon. Together, this shows that ocean CDR has a substantial ability to scale.

Ocean CDR innovations are in the early stages of research and development, with most innovations occurring in a laboratory setting and some companies conducting early field trials. These efforts are important, but in order to move from the lab to deployment, widespread field tests are necessary to understand and validate the effectiveness in a real ocean environment. Today, real-world ocean CDR tests are nearly impossible to conduct in the U.S. due to unclear regulatory processes and laws. Additionally, situations with existing regulatory frameworks, that may include CDR activities, require an arduous and opaque permitting process. For instance, early field trials in the U.S. are being performed by start-ups like Planetary through wastewater permits, and Vesta through beach restoration. Without changes and clarifications, the current U.S. regulatory processes and laws pose significant challenges for full-scale deployment of ocean CDR and could send U.S. innovators to develop and deploy in countries with more favorable regulatory systems.

We are beginning to see this happen. Planetary, whose technology was originally conceived at the Lawrence Livermore National Labs in California, has focused work in the United Kingdom and Canada, in part due to different in-ocean regulations. A clear and predictable U.S. regulatory process for ocean CDR pathways is needed to ensure that America can lead the world in ocean CDR research, development, and deployment (RD&D).

The ocean’s natural chemical adjustment system removes CO2 from the atmosphere to balance the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and the ocean. Therefore, with increasing atmospheric CO2, the ocean absorbs more CO2, which leads to ocean acidification, which has impacted ocean health, and has reduced the ability of the ocean to act as a carbon sink. Ocean CDR pathways are a potential method to deacidify the ocean to maintain its crucial role in global carbon sequestration.

Source: NOAA

*The State of Carbon Removal of 2023 report estimates alkalinity enhancement upper-bound to be 100 Gt CO2 removed per year.

** The mean seawater residence time of alkaline dissolved carbon is about 100,000 years, based on the annual input of alkaline carbon from rivers (0.3 GtC/yr), the alkaline pool of dissolved alkaline carbon resident in the ocean (about 34,000 GtC), and assuming steady state.

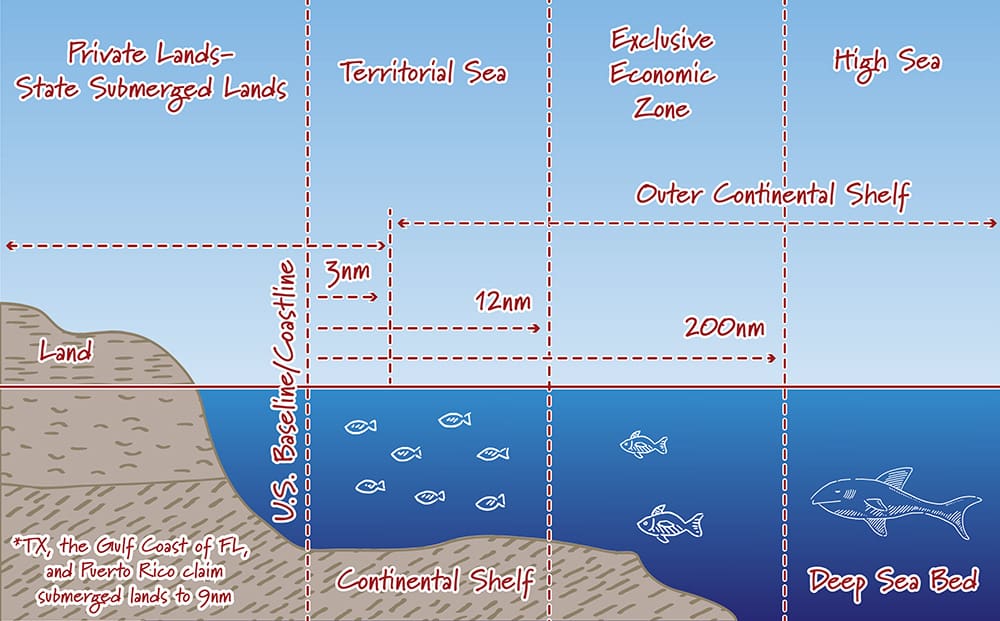

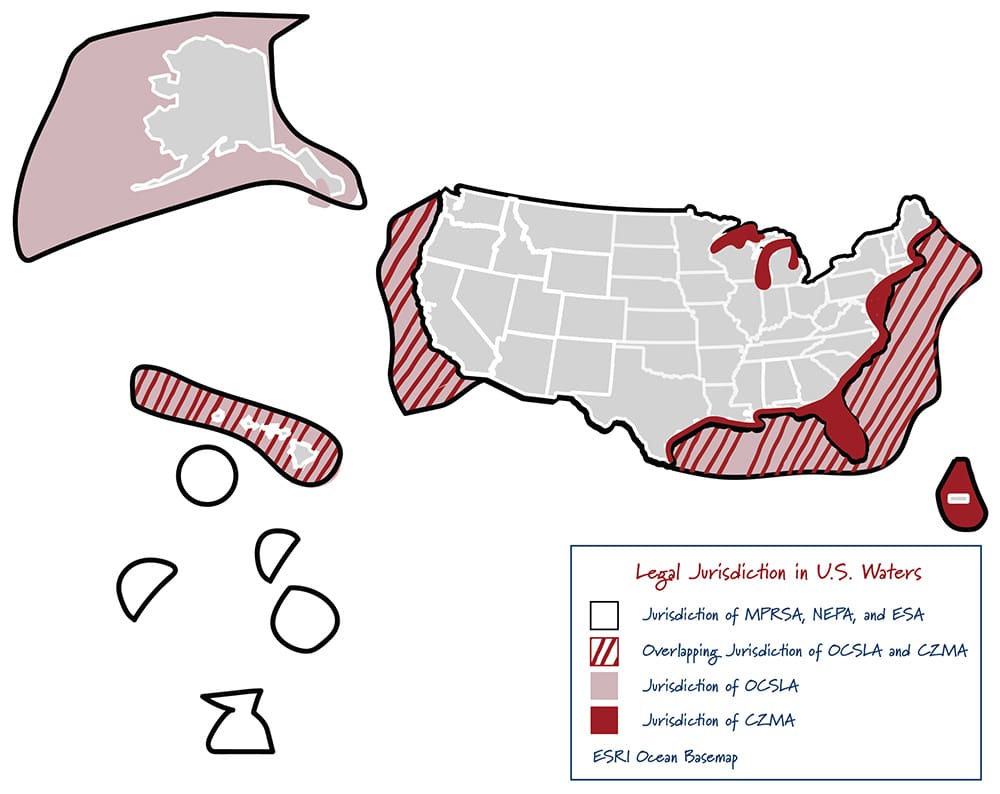

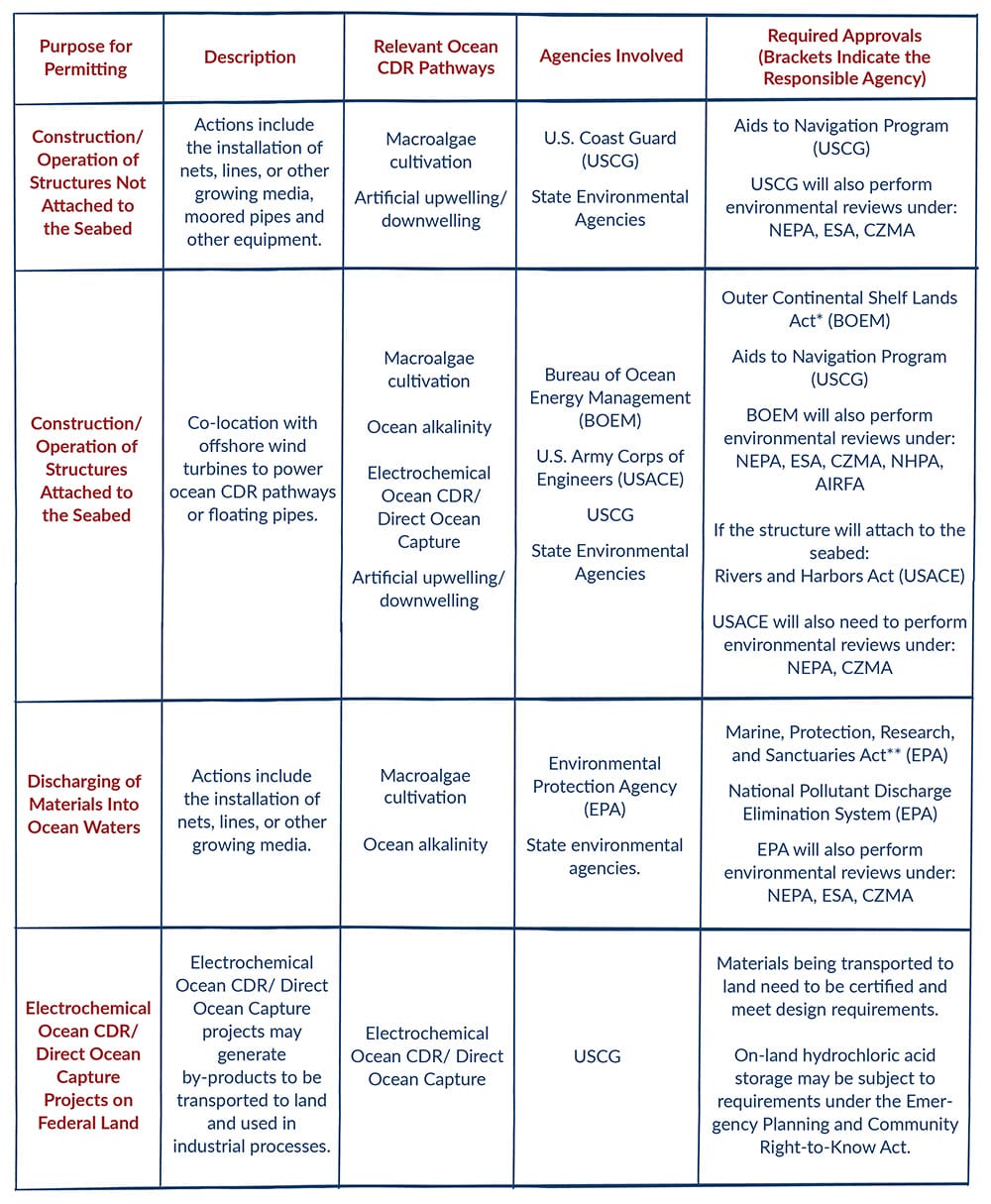

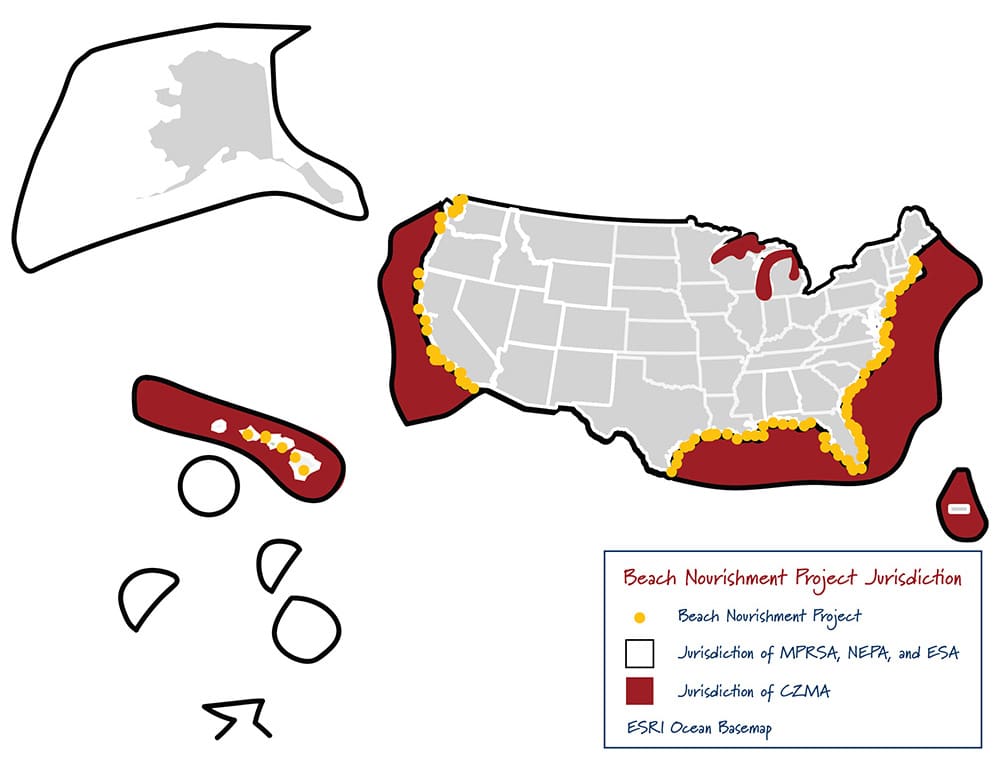

Some technologies may require the installation of structures onto the seafloor in the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), outlined in Figure 1. Other projects may sink materials to the ocean floor within the U.S. waters but outside the OCS. Each of these pathways is governed by different laws, and innovators lack the clarity needed to proceed with testing. The legal jurisdictions of federal U.S. waters are highlighted in Figure 2, and the locations of existing beach nourishment sites described and presented in the Appendix.

Updates to the regulatory process should be made to ensure timely and transparent regulatory processing while addressing any risks.

Source: NOAA

Sources: NASEM, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law reports on Seaweed Cultivation and Ocean Alkalinity.

Research and Development

The following laws may impact ocean CDR pathways depending on the location of projects (see Figure 1). Projects within state waters, typically up to three nautical miles from the coast, but nine nautical miles from Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico, may be subject to state and/or local laws. Federal laws will apply to projects in federal waters, up to 200 nautical miles beyond state waters, while some projects may require additional activity on federal lands.

Seabed Use Laws

Ocean Discharge Laws

Environmental Review Laws

Coastal and Ocean Management Laws

Species Protection Laws

Other Laws

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) protects and preserves American Indian access to sites, use, and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship.

Sources: Marine Cadastre

Beach nourishment is the process of adding large quantities of sand or sediment on a beach or in the nearshore, often to combat erosion and increase beach width. The length of total coastlines with beach nourishment is 962.4 miles. Florida has a fifth (~21%) of all projects. The ocean CDR start-up, Vesta, is implementing a beach nourishment project at North Sea Beach in the Town of Southampton. This project includes Coastal Carbon Capture, to advance climate science research, by placing olivine sand onto the North Sea Beach Colony frontage. Olivine is used for enhanced weathering, because it is a common and naturally occurring silicate material that removes carbon dioxide when it dissolves in water, and permanently stores it in the ocean as carbonate and bicarbonate.