Hydrogen is the smallest element on earth, but it can potentially impact the power, manufacturing, and transportation sectors by maximizing resources in the overall energy system. Currently, hydrogen is primarily used for petroleum refining and fertilizer production, but it could also be stored for seasonal energy security, burned as a low-emissions heat source, turned directly into electricity, or used in chemical production. Every year, the United States produces around 10 million metric tons of hydrogen – enough to power 2.4 million transcontinental flights for a Boeing 747. This may seem like a lot, but it only equates to the energy of about 12 days of U.S. natural gas production in 2022.

To address the cost barrier of clean hydrogen, the Department of Energy (DOE) launched the Hydrogen Shot “1-1-1” goal to reduce the cost of producing hydrogen to $1 per Kg within one decade, which is an 80% decrease from 2021 costs by late 2030.

Outside of cost, simultaneous development of the hydrogen value chain (i.e., production, storage, end-use) is a barrier to deployment due to varying levels of technological readiness, lack of long-term offtake, and need for infrastructure to store and transport hydrogen. To address this challenge, the bipartisan Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA) of 2021 established the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs (H2Hubs) program, so that each regional hub could develop all aspects of the value chain simultaneously. For strategic implementation of the H2Hubs, the DOE released the U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap, which identified the highest-impact industries that could have significant emissions reductions using hydrogen. Furthermore, because hydrogen is an enabling technology for the power, manufacturing and transportation sectors there are a number of agencies involved in its development and commercialization. The Hydrogen Interagency Taskforce (HIT) was established to coordinate federal agencies’ efforts to reach the roadmap’s goals.

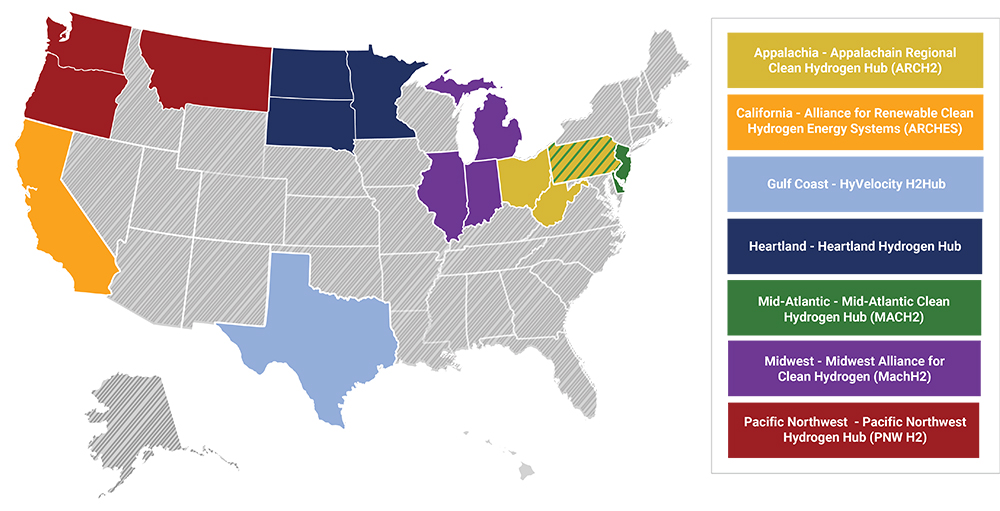

In October of 2023, the DOE preliminarily selected seven public-private partnerships to receive awards for the H2Hub program authorized by the IIJA. The $8 billion program will help launch the nascent hydrogen industry forward and decrease the cost of clean hydrogen.

Figure 1. Map of states selected for the DOE H2Hub’s award negotiations. Negotiations are expected to be completed in Q2 of 2024.

Hydrogen can be an innovative solution for the power, manufacturing and transportation sectors, capable of reducing emissions while making American energy cleaner and more secure. Tech-neutral policies that encourage investments in midstream infrastructure develop reasonable regulations, and build upon the regional hydrogen hubs can increase hydrogen’s impact on emissions.

Develop policies that encourage and incentivize diverse, low-emission hydrogen production methods. Wherever possible, policies should be technology-neutral, rewarding low-emissions hydrogen production regardless of whether it is generated by natural gas with carbon capture, renewable energy, biomass, nuclear energy, or other innovative solutions.

Advance policies that further expand and decrease the cost of midstream and end-use infrastructure. For hydrogen to be a viable emissions-reducing tool, the delivered cost of hydrogen must significantly decrease by increasing the availability of midstream infrastructure. Distribution and storage can more than double the cost of hydrogen for end-users. Today, the U.S. has about 1,600 miles of dedicated hydrogen pipelines; mostly located in Texas and Louisiana. Several of the H2Hubs have publicly announced the intent to build pipelines. It is vital that these deployment teams build with the future in mind since they will be laying the foundation for hydrogen availability and market expansion. For hydrogen to be prevalent enough to help meet national climate targets by 2050, the DOE anticipates 30% of all hydrogen investment costs will be in midstream infrastructure between 2030 and 2050. Moving forward, research and development (R&D) priorities should be balanced within the DOE to lower costs and encourage midstream development.

Develop reasonable regulations in preparation for a mature and scaled industry. Federal regulations do not currently exist for the interstate siting of hydrogen pipelines. In the near term, companies siting interstate pipelines will be able to coordinate with individual states. However, for widespread adoption, clarity around federal interstate pipeline regulation would create certainty for investors and expedite private investment. In the meantime, any advancements to streamline project permitting and siting would allow for more efficient midstream infrastructure deployment. Additionally, developing codes and standards for hydrogen blending into natural gas pipelines could accelerate adoption. Guidance surrounding hydrogen storage (i.e., the ability to store hydrogen in underground salt caverns) would allow developers to make long-term decisions sooner.

Improve the cost-competitiveness of clean hydrogen. At the DOE Hydrogen Shot Summit in 2021, 22% of the 3,000 attendees identified “cost to end user” as the number one barrier to hydrogen deployment. To reach the DOE’s goal of $1/kg by 2030, capital costs must be reduced by 80% and operating and maintenance costs reduced by 90%. To help lower costs, the U.S. Department of Treasury is in the process of developing the guidance for the hydrogen production tax credit (45V), which is expected by the end of 2023. In order for nascent hydrogen technologies to scale rapidly, the guidance needs to aid industry in commercializing technology by lowering the cost of production.

Support reliable offtake for hydrogen producers. The DOE Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations is developing a demand-side mechanism to support reliable offtake for projects in the H2Hubs program. During the selection process, it became apparent that the expected reduction of production-cost was disincentivizing long-term offtake contracts, creating revenue uncertainty and delaying final investment decisions. An additional mechanism, within existing authorization and using existing funds of the H2Hubs, can support private financing for clean hydrogen projects and increase the likelihood of success of hub deployment.

Over the past few years, policymakers have made significant investments in the future of American hydrogen, including the following: