Posted on May 11, 2023 by Nick Lombardo

The dual imperatives of addressing energy security and climate change are inherently international. The world needs more energy, and emissions know no borders. ClearPath sees a future where America and like-minded partners lead the world in addressing climate change by developing and deploying the most innovative, market-competitive clean energy technologies. U.S. emissions are a smaller and smaller part of the global total, now roughly 11%, which emphasizes the need for the U.S. to work effectively with international partners and allies because our efforts at home will not be enough to solve our energy and climate challenges alone.

The U.S. has built a good track record, AND we need to do more.

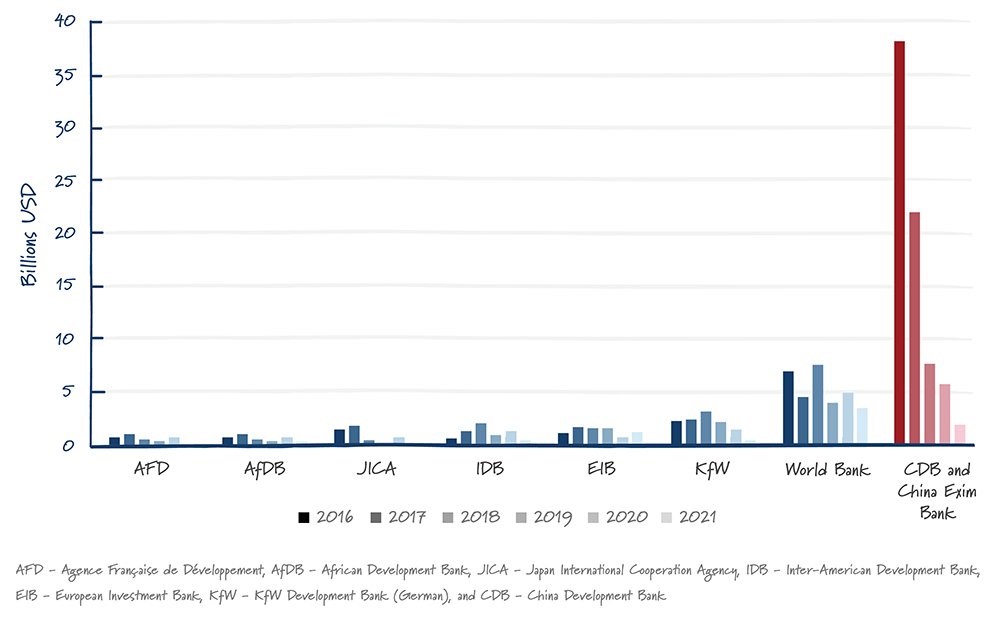

We must be clear-eyed about the intense global competition the U.S. faces. For instance, since 2000 China has become a dominant player of global energy finance, issuing over $234 billion in loans for energy projects to roughly 68 strategically-significant nations, with about 75% of that directed towards coal, oil, and gas development. For perspective, from 2016-2021, China provided more energy project financing around the world than all major Western-backed Multilateral Development Banks combined. In order to compete effectively, the U.S. needs to make better use of the policy tools we already have, and design new ones.

Energy Finance Commitments by Major Development Finance Institutions, 2016-2021

Official project databases of each development finance institution (DFI); China’s Global Energy Finance (CGEF) Database, 2022. Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

Some of the most impactful tools in America’s toolkit are international trade and financing policies, and this is nothing new. Institutions like the U.S. Export Import (EXIM) Bank were established in the wake of World War II, engaging in the reconstruction of Europe and Japan, then evolved in the 1950s and ‘60s to help American exporters gain a foothold in emerging markets and later supported large-scale infrastructure projects in the ‘70s. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan signed the United States’ first free trade agreement into law, the U.S.-Israel Free Trade Agreement, which helped America solidify one of its closest strategic partnerships that now spans nearly every domain including commerce and clean energy technologies.

The world has changed a lot since the Reagan era. The expansion of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine have underscored the need for United States international leadership, not only for our own energy security, but also that of our partners. This can be supported through exports and financing of technologies that reduce reliance on adversarial nations while reducing emissions. Concerted action with our partners and allies through trade and financing can be an essential counterweight to other nations that do not have our best interests, nor the world’s climate, at heart.

A recent example of the strategic role that American financing can play for clean energy is the development of Poland’s first nuclear plants. The Trump Administration led a key Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) between the U.S. and Poland to develop Poland’s civil nuclear power program and industrial sector. That agreement clearly articulated America’s intention to leverage the U.S. EXIM Bank and other government financing institutions for Polish reactors. Subsequently, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) funded an initial engineering study for Poland to assess the viability of Pennsylvania-based Westinghouse Electric Company’s AP1000 reactor technology. These efforts culminated in November 2022 when the U.S. Government tabled a comprehensive, competitive technical and financing package, and the Polish Government chose Westinghouse’s reactor, in a deal worth roughly $40 billion. Building on that, in April 2023 EXIM and the U.S. Development Finance Corporation signed an agreement to finance up to $4 billion for another Polish project that could support the U.S. export of GE Hitachi’s small modular reactors. These kinds of projects bring geostrategic, economic, and climate benefits to the people of Poland and the United States, and are made possible by the backing of American financing.

Painstakingly negotiated trade agreements, like the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), are also an important lever to promote high-standards American industrial practices abroad. Among the provisions of USMCA are enforceable requirements for Canada and Mexico to effectively implement their environmental laws, including air quality and emissions, without weakening those laws just to promote their own exports and investment. Other provisions commit the countries to enhancing trade and investment in environmental goods and services, including clean energy technologies, by eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers. Agreements like these can help create the economic conditions to support clean technology innovation and deployment, while establishing a bulwark against nations that do not adhere to such standards. America’s network of trading partners is a powerful dimension of global leadership and should be continually expanded and improved, in part, to help combat environmental arbitrage.

Both the example of Poland’s civil nuclear program and the USMCA – initiated under conservative leadership and implemented in a bipartisan manner – took years to come together. Unfortunately, this type of coordinated effort across U.S. federal agencies is the exception not the norm. Many of the best tools, such as the Development Finance Corporation, are often disconnected from the rest of the government financing tools and clean energy goals. This is not an effective way to compete with rival countries where there is far more strategic alignment across agencies and often their non-market, state-owned enterprises.

That’s why we need to better leverage existing tools and build new ones in order to reach our future clean energy and climate ambitions.

A good example of a needed fix is EXIM’s China Transformational Exports Program (CTEP). This program has a Congressional mandate for EXIM to support U.S. exporters facing competition from China in 10 key Transformational Export Areas. One of those export areas is “renewable energy, energy efficiency, and energy storage.” Conceptually, the program could be a valuable lever for all clean energy technology providers (and the financing needs of foreign customers) facing unfair competition. But unfortunately – to the detriment of our geopolitical, clean energy, and climate goals – limiting this program to renewable energy sources alone leaves out important technologies like advanced nuclear, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and hydrogen. In an all-of-the-above energy competition with China, CTEP deserves a common-sense revision to be more technology neutral when it comes to clean energy if we’re serious about competing and winning on exports and against climate change.

For years the United States led negotiations on a high-standards Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) to lower trade barriers on clean energy technologies. Although the negotiations were not completed, significant progress was made. For many of the clean energy products previously under consideration for an EGA U.S. tariffs are already very low compared to tariffs American exporters face in foreign countries. Accordingly, an EGA would help open international markets to U.S. clean energy technologies that are being rapidly demonstrated and deployed. An ambitious EGA would reduce the price of U.S. clean energy abroad, helping other countries lower emissions affordably while supporting American jobs. There has been recent bipartisan interest in pursuing a new EGA to help modernize the global trading framework, and the U.S. should seriously consider getting back to the negotiating table.

Clean Energy + Trade = Jobs

These are just a couple examples as to why every tool in our policy toolkit should be available – and sharpened – to address massive global challenges like energy security and climate change. No nation will use a single clean power technology, every country will need to find the right mix given its national circumstances, geography, resource endowments, and pre-existing industry. Our competitors are bringing enormous resources to bear in an effort to dominate these markets, which requires the United States to be more agile and strategic in order to advance our long-term goals. But with the right policies in place, and in coordinated action with partners around the world, our energy and climate future will be bright, at home and abroad.