Posted on January 15, 2026 by Jake Kincer , Bryson Roberson, Cason Carroll and Austin Blanch

The United States is entering an era of rapidly growing power demand, driven by a manufacturing boom and the adoption of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence. To keep up with this heightened demand, companies are seeking to deploy more generation to ensure electricity availability, reliability and affordability. In response, power utilities and state governments are beginning to treat nuclear power as essential infrastructure.

While some state governments enacted bans or limitations on nuclear power in recent decades, many have already begun to reverse course in order to compete in the energy race. Increasingly, state governments are exploring how to work together to create the conditions for successful and timely deployment of new nuclear reactors.

Deploying a fleet of new nuclear power plants is a tall order, which makes coordinating the resources of multiple states an attractive option. However, doing so requires navigating a highly complex legal and regulatory landscape as well as the physical infrastructure of the U.S. power grid. The concept of an “interstate compact” itself opens legal questions related to the Compact Clause. In practical terms, any collaboration will need to account for market and regulatory differences, or even the lack of appropriate physical infrastructure. Overcoming these challenges will require careful negotiation to find a model capable of pushing nuclear deployment forward. This piece reviews U.S. power system management and offers suggestions on how to construct interstate agreements effectively to accelerate these deployments.

The U.S. Power System

Collaborative efforts between states to deploy new nuclear, through interstate agreements called compacts, are not a new concept. Hundreds of compacts are used to address various policy issues. These agreements allow states to utilize resources efficiently by sharing expertise, financial resources, supply chains or other means, depending on the policy issue.

Utah, Idaho and Wyoming signed a tri-state agreement to support nuclear energy deployment last year. Collaboration on nuclear energy is particularly fitting for these states because they share energy infrastructure, have similar energy profiles and face comparable geographic constraints:

With utilities across the West joining different markets, including in Utah, Idaho and Wyoming, there is potential to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of joint nuclear energy development. Shared challenges and individual strengths create a robust foundation for collaboration. States can bridge gaps in infrastructure and expertise by leveraging National Lab resources and existing nuclear expertise in one state, while co-developing regional manufacturing and workforce pipelines that can support new nuclear across several states.

Many states are beginning to address shared opportunities through state-supported feasibility studies or by considering programs to either repurpose their existing workforce, by creating, improving or expanding specialized education systems, or supporting an influx of workers with existing, necessary experience. Aggressive and intentional state-level policy to support early deployment of nuclear energy sends a strong signal to developers, but may not be enough to overcome challenges with early project deployments. Regional agreements could allow states to share and expand these resources collaboratively and more efficiently, or form a “buyers club” across similar markets to help spread the risk of early deployments.

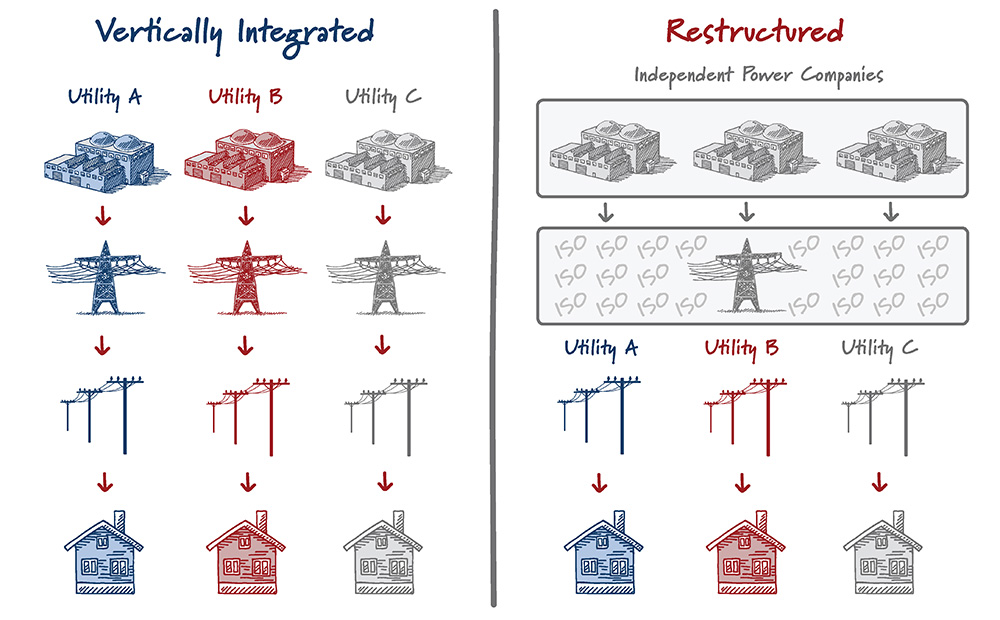

State energy market structures impact the commercialization path of nuclear projects. In a state with vertically integrated utilities, states can enact advanced rate recovery mechanisms to recover costs in real time rather than waiting until a plant is operational. The upfront revenue reduces the amount that needs to be borrowed and the total interest cost during construction.

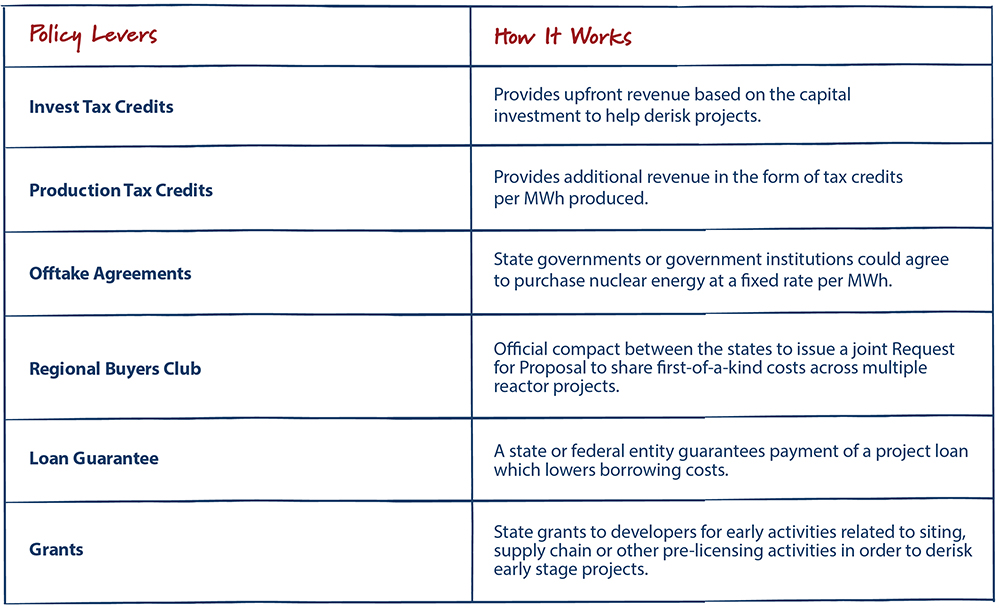

Conversely, generation, transmission and distribution are separated in a state with restructured utilities, and generators earn revenue by selling their electricity into the competitive market. With most utilities procuring their electricity from the market and other entities that own the generation, advanced rate recovery isn’t an option. To make early nuclear reactor deployments financially viable in a deregulated market, multiple policy levers and financial contracts will likely need to be stacked to supplement the wholesale market revenue once the nuclear reactor is sold into the marketplace.

A collaborative effort between, for example, deregulated states with existing nuclear energy (e.g., OH, PA, MD, CT and NY) could pull multiple levers in tandem to see new nuclear development in their state.

These include:

Example Policy Levers

Regardless of market structure, it is common for utilities to own generation assets in one state serving customers in another. Decisions on where to locate generation assets are built on factors including power needs, resource availability, environmental considerations, regulatory requirements, cost and policy incentives. Utility Integrated Resource Plans (IRPs) will have to consider all of these aspects when planning to build out new nuclear.

State-level recognition of nuclear energy as a clean energy source also significantly impacts project viability and access to funding. Some states, such as Virginia and Maryland, have Renewable Portfolio Standards, and later clarified that nuclear energy would count toward those goals. Other states have adopted technology-agnostic Clean Energy Standards that focus solely on zero- or low-carbon goals. By ensuring that existing state statutes consider nuclear technology on a level playing field with other technologies, states can enable nuclear projects to qualify for certain loans, grants and other funding opportunities that might otherwise be unavailable.

Effective nuclear deployment also hinges on robust, efficient and predictable federal oversight. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is the independent federal agency responsible for overseeing and regulating civilian nuclear energy and nuclear materials. Before operation, nuclear power plants must undergo NRC safety, financial and environmental reviews for their construction and operating licenses.

Beyond direct NRC licensing, the Interstate Compact Clause is an important federal dynamic to consider. Stemming from the landmark case Virginia v. Tennessee (1893), this clause draws a line requiring Congressional approval for a certain level of collaboration between states. This will not categorically prevent states from working together, but it complicates the types of collaboration possible and may require states to seek congressional approval.

Even with effective policies and regulatory frameworks, a significant barrier to certain regional agreements and broader nuclear deployment can be physical: moving electrons requires significant transmission capacity and transfer capability, a major constraint for all kinds of energy development in the U.S. Though projects to improve connections both inter- and intra-regionally are underway, these infrastructure limitations will remain a primary consideration for nuclear deployments; it may not be physically possible to move sufficient power from one area of a state to another, especially if significant distance or geographic barriers are present. These limitations could become the subject of state-to-state collaborations.

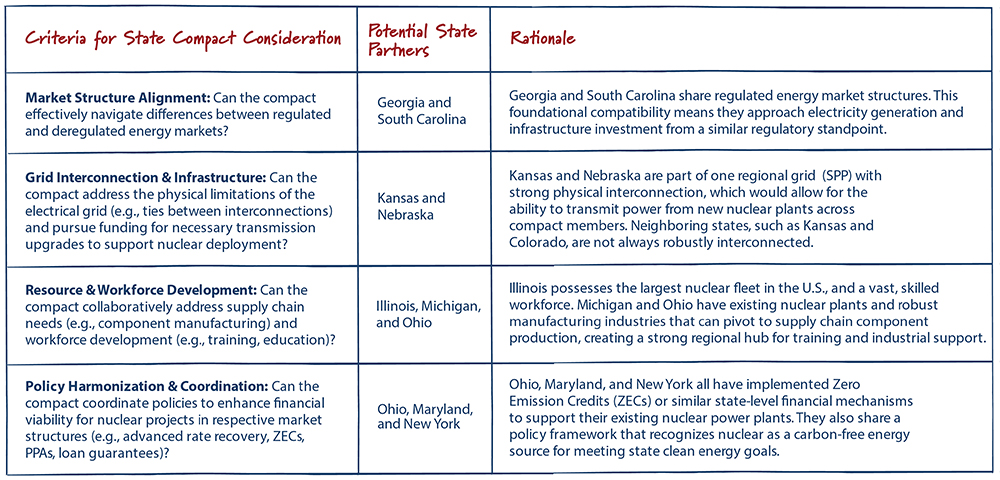

Several factors can affect states’ success as they seek collaborative agreements. Below is a table with examples of how these factors may impact certain regions. States should consider the weighting of each category, as individual factors will significantly matter.

Examples of Alignment for State Collaboration

Nuclear energy has a long-standing history with interstate compacts around low-level radioactive waste across the nation and the Western Interstate Nuclear Compact. As identified previously, these compacts require congressional approval, so less formal agreements may be preferred.

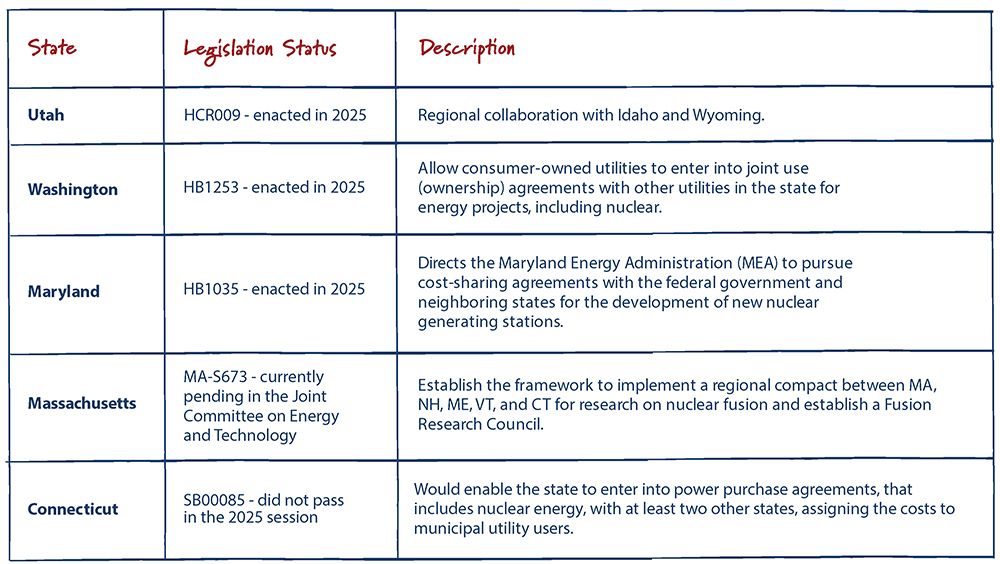

Memoranda of Understanding or other Regional Energy Initiatives, such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission and the Western Governors’ Association, serve as forums for states to support each other in regional energy policy. Over the past few years, various states have worked to push projects and legislation with varying degrees of success with interstate partners.

Examples of Supportive State Legislation Proposed or Passed in 2025

Achieving widespread nuclear energy deployment will hinge on initial order books of five to 10 units of the same design being committed to and financed as soon as possible. States, working together, can lead by sharing the risk of a first-of-a-kind reactor through strategic partnerships. This initial step will pave the way for the commercialization of new nuclear reactors driven by economies of scale.

State collaboration offers a strategic lever to catalyze momentum. By joining forces across multiple regions, states can sync project timelines to support workforce and supply chain needs in the construction phase. Pooled demand will amplify the market signal to developers and supply chain industries, especially if states enter formal agreements. Participating states can collaborate on workforce training and retraining, standing up qualified supply chains, aligning regulatory requirements and siting and approval challenges. Regional collaboration can create a unified voice to advocate for federal support.

However, the challenges of achieving an interstate compact, especially one that can accomplish the goal of creating an orderbook of new nuclear, should not be understated. States will need to carefully consider the type of collaboration they want to pursue and identify the partners best suited. If successful, regional collaboration could be a powerful lever to usher in the next wave of nuclear projects and drive a national strategy to dramatically increase American nuclear capacity.

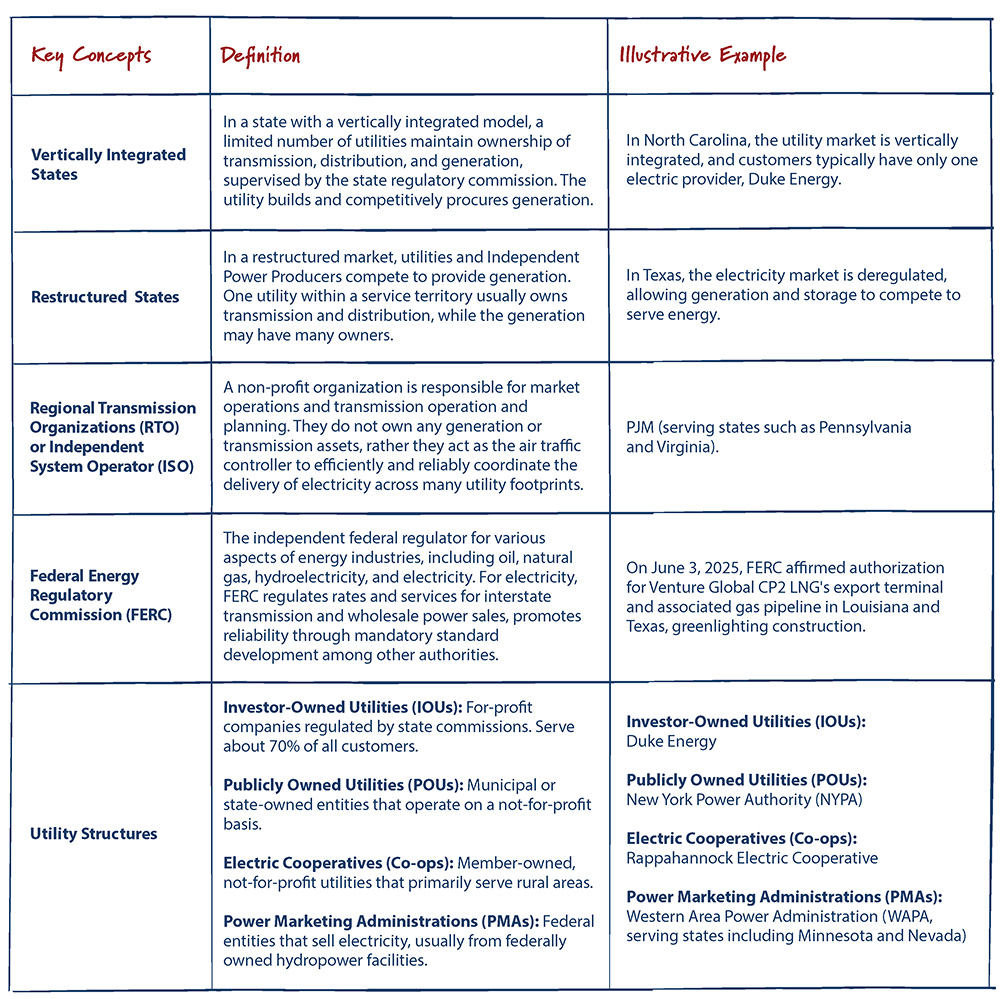

Key Concepts in the Governance of the U.S. Power System

Bryson Roberson is a former ClearPath Conservative Leadership Program Fellow. He is now a Legislative Correspondent for Senator Dave McCormick (R-PA).

Cason Carroll is a Program Manager at Envoy Public Labs.

Austin Blanch is a Senior Analyst at Envoy Public Labs.