Posted on November 8, 2023 by 240 and Matthew Mailloux

Over the course of this year, Congress wrestled with big permitting questions. House Republicans passed H.R. 1, the Lower Energy Costs Act, earlier this year with bipartisan support and some of the provisions from H.R. 1 were included in the debt ceiling deal codified by the Fiscal Responsibility Act. Yet, after it passed, the Biden Administration’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) released questionable guidance on how to implement those provisions through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). House Republicans and Republican Governors alike rightly questioned CEQ’s plan.

To be clear, energy permitting is still stuck in permitting purgatory and tied up in red tape. Needless to say, the recent CEQ guidance certainly did not fix the problem. Currently, one of the biggest areas to address is how permits for energy infrastructure can be challenged in court. Before construction can begin, these facilities must undergo permitting at the local, state and often federal level. And where there are permits required, court challenges can quickly follow.

There are numerous proposals in Congress to address these well-documented hurdles in the current litigation process. H.R. 1 included two frequently discussed proposals that would raise the bar for entities that wish to file suit, by requiring participation early in the permitting process and then reduce the length of time after permits have been issued for an entity to file a legal challenge. It is important to preserve access for everyone to have an opportunity to be heard in a dispute and to reach a resolution, for or against, but it’s equally important to do this in a timely manner. Specifically, how the U.S. can adapt the current litigation process to reach finality on a predictable timeline.

Another set of potential solutions are included in the Revising and Enhancing Project Authorizations Impacted by Review (REPAIR) Act (S. 3170) introduced by Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) in October 2023. The bill would establish new requirements to file a legal challenge to a permit by setting timelines to file challenge, eliminating venue shopping, and empowering the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC) to mediate permits remanded by a court. These are all tangible actions congress could take to streamline permitting litigation.

Another way to address permit challenges is already in place in many Executive Branch agencies—such as The Environmental Appeals Board (EAB) at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of the Interior Board of Land Appeals (IBLA) – and can adopted for energy infrastructure projects to provide the same certainty to all in a timely manner.

These quasi-judicial boards are composed of subject matter expert administrative law judges and magistrates review permitting decisions and other federal actions. Furthermore, these existing boards have long track records, with the EAB established back in 1992 as an impartial appellate tribunal within the EPA to resolve administrative appeals of certain environmental disputes arising under the major environmental statutes that the EPA administers.

For the EPA, its Administrator has delegated authority to the Board to hear these appeals. The EAB hears permit appeals related to major environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act (CAA), Clean Water Act (CWA), and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), among others. The EAB has issued over 1,100 final decisions. In most instances, the Board’s involvement has resolved the dispute, thereby promoting efficiency by avoiding protracted and expensive litigation in federal court.

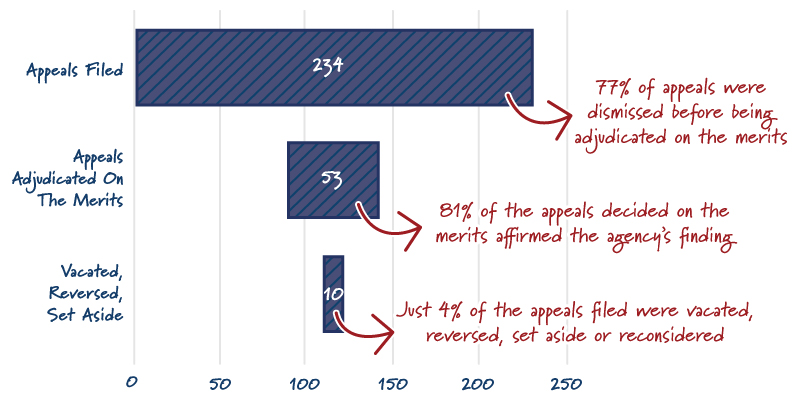

Based on the most recent data from the IBLA, the vast majority of challenges are dismissed before they are ever adjudicated on the merits. For the remaining cases that do move forward, an even smaller share ultimately leads to permits being vacated, reversed or set aside.

Most Appeals to the IBLA Are Dismissed, and Just 4% Change the Agency’s Initial Findings

The benefit to the IBLA model is that the administrative law judges who hear these cases are subject matter experts, narrowly focused on the work of the permitting process. Contrast this with a federal district court judge who may bounce from a capital murder case to a trademark dispute to a narrowly focused permitting question.

It takes substantial time to build the evidentiary record in these cases, which can stretch legal challenges out for an uncertain length of time–often for years when appeals are factored in. By contrast, administrative law judges can serve an effective role in these narrowly focused permitting disputes. By using the agency’s administrative permitting record as the basis for their review, these challenges can be addressed on a more predictable timeline.

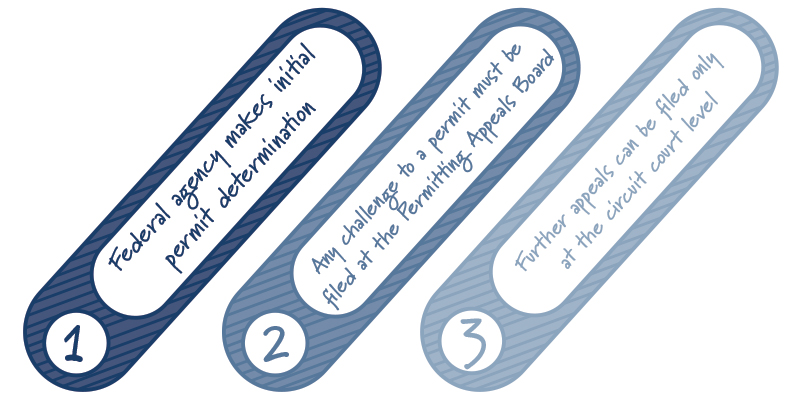

Expanding this model to energy infrastructure projects offers an opportunity to leverage these types of decision-making bodies to apply to all permits that are challenged at the federal level. This can be accomplished by creating a new centrally located Permitting Appeals Board, either as a standalone agency or at the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC).

To go a step further, the appeals process could mirror provisions similar to those in the Federal Power Act and Natural Gas Act where any further challenges to a permitting decision must be appealed directly to the appellate courts. This would further empower the decision-making authority of the Permitting Appeals Board and eliminate the repetitive process that currently exists when appeals of EAB or IBLA decisions are brought before district courts.

Simplify Permits and Appeals Into a Clear, Predictable Three-Step Process

Given these boards are not constitutionally chartered courts, Congress would have much more authority to set and enforce timelines and clearly define the criteria for review compared to a coequal branch of government.

By finally making the judicial review process for energy infrastructure in a more streamlined manner — removing the long delays of sending litigation to court — it will allow project financing decisions much easier. Reaching finality on legal challenges on a predictable timeline is the greatest lever Congress can pull to start getting America building again. Unlike the current system when legal challenges can stretch on for a decade or more, implementing proposals like those included in the REPAIR Act and establishing a permitting review board would reliably resolve these challenges in under one year.