Posted on March 13, 2025 by Kelsey Grant

Pipelines are critical infrastructures that move essential resources, such as water, oil, natural gas and other materials, from where they are produced or gathered to locations where they can be used or stored. Pipelines are everywhere. They are found beneath our highways, through our cities and communities. If you have a gas stove or plumbing, you have a pipeline in use at home. Today, there are over 5,300 miles of carbon dioxide (CO2) pipelines in the United States.

For over 50 years, pipelines have transported CO2 safely, quickly, efficiently and in large volumes. This experience makes pipelines uniquely equipped to facilitate the deployment of carbon management technologies such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and direct air capture (DAC).

Carbon management technologies drive clean energy innovation and job creation at home, while strengthening U.S. global competitiveness and energy leadership abroad. The U.S. government has already invested billions in carbon management technologies, and from 2022 through mid-2024, the private sector announced over $26 billion in investments in these technologies.

Today, more than 270 carbon management projects have been announced that are at various stages of development or are operational in the U.S. These projects make pipeline infrastructure essential. When CO2 is captured, it’s often not located near an available storage or use site and has to be transported to another location. Over half of cement plants in the U.S. are located outside a 100-mile radius of the nearest CO2 storage site. Pipelines are the best and safest way to move CO2 to these storage sites and other locations.

In this 101, you will learn about CO2 pipelines, including the importance of pipelines for U.S. energy security, how CO2 pipelines are regulated, why they are safe, and most importantly, policies that can enable the build-out of this infrastructure.

Recommendations include:

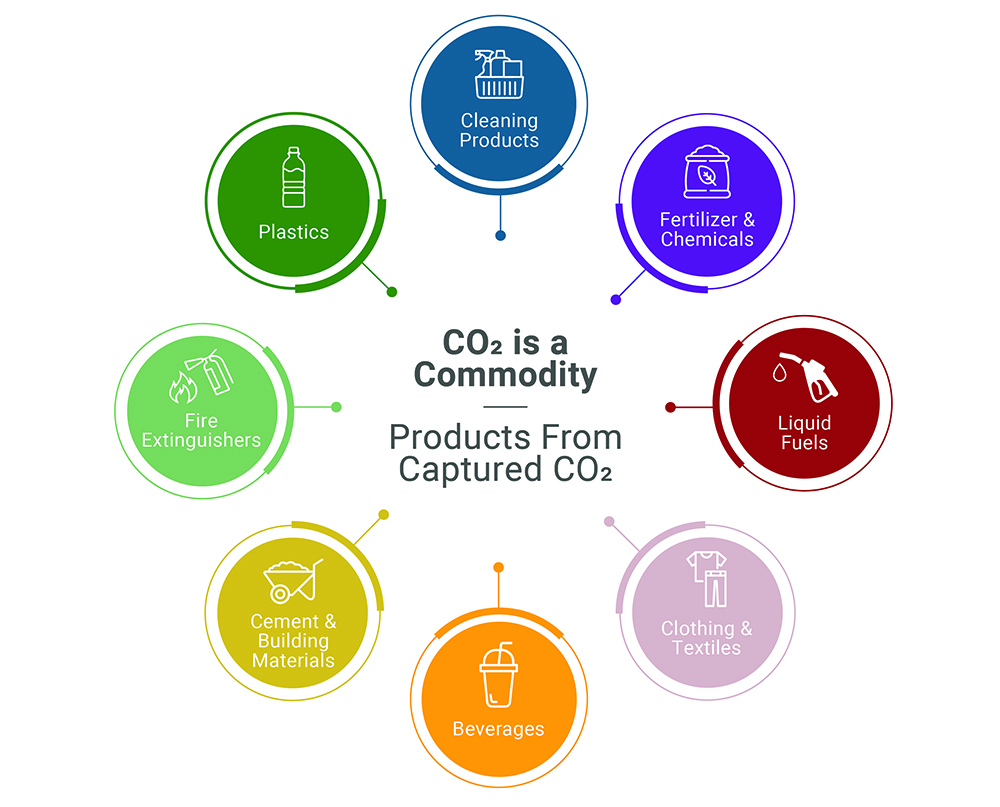

CO2 pipelines move carbon dioxide – a non-flammable, odorless and stable gas – to locations where it can enhance energy production, make valuable products or be safely stored. CO2 is usually transported in a liquid or “supercritical” state, which is the easiest, most efficient way to transport CO2. A supercritical state means the CO2 is pressurized to the point it exhibits properties of both a liquid and gas.

Like most pipelines, CO2 pipelines are primarily located underground and out of sight. They are made with high-grade steel paired with anti-corrosive coatings and typically have a diameter of 4 to 24 inches – which is roughly between the length of a cell phone and a carry-on suitcase.

CO2 pipelines have been safely operating in the U.S. for the last half-century. Historically, most CO2 pipelines in the U.S. have transported CO2 for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations. EOR is a highly engineered, well-understood process where CO2 is injected into the reservoirs of an existing oil field to increase oil recovery from depleting wells. During these operations, CO2 can remain underground, keeping it out of the atmosphere.

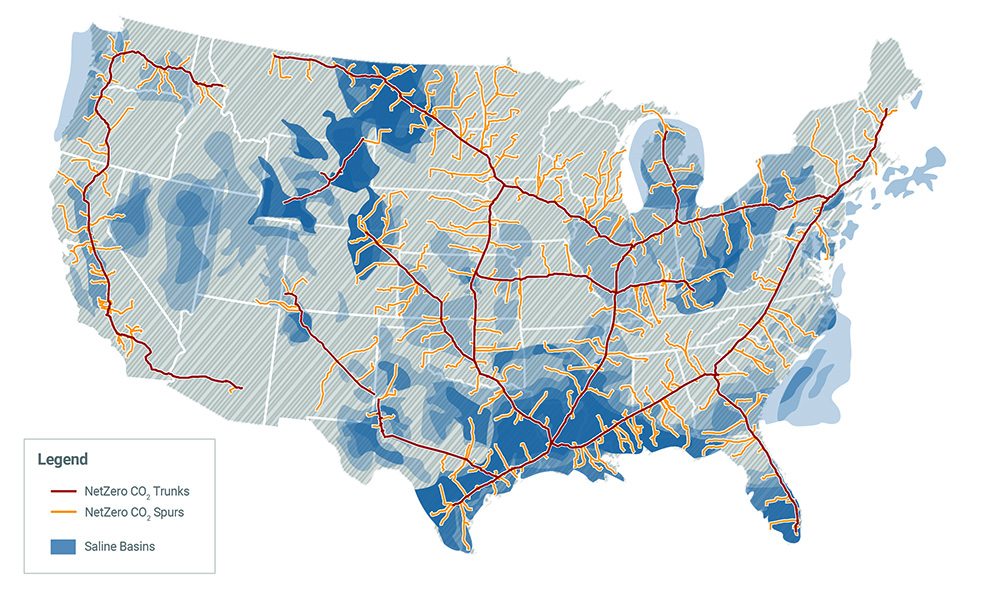

Of the 5,300 miles of CO2 pipelines across the U.S., most are in Texas, New Mexico, Wyoming, Oklahoma, Louisiana, North Dakota, Mississippi and Colorado. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, an estimated 30,000 – 96,000 miles of CO2 pipelines will be needed by 2050 to reach our emissions reduction goals. To put these numbers in perspective, this is only 1-3% the length of our existing 3,000,000 miles of oil and gas pipelines in the U.S. today.

Illustrative 2050 CO2 Pipeline Network

Sources include ClearPath analysis, National Carbon Sequestration Database Saline basins, and Princeton’s Net-Zero America spur and trunk line transmission expansions for the high-electrification scenario.

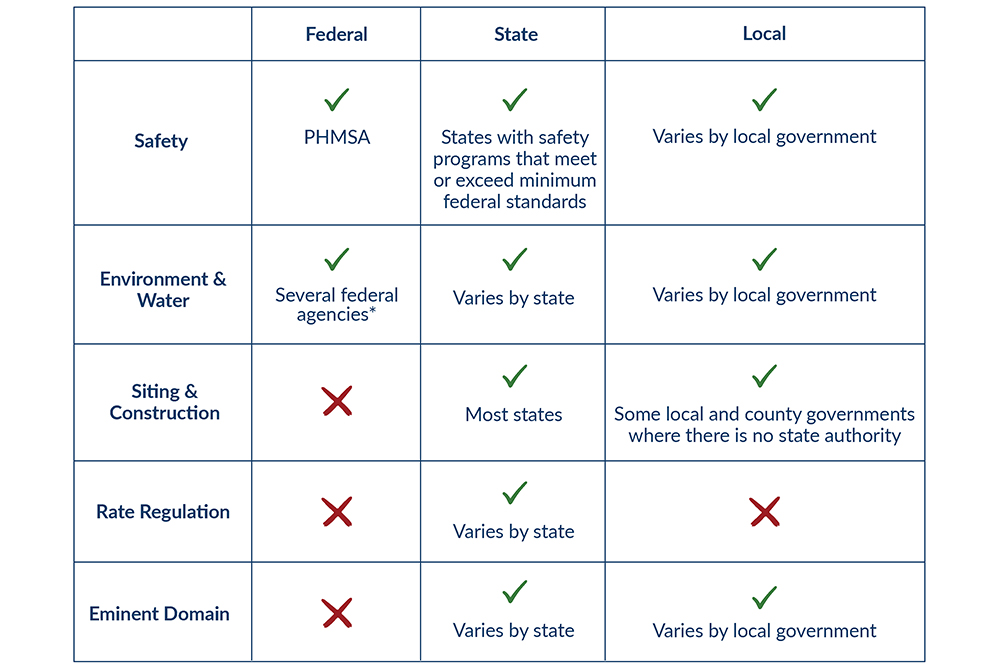

Similar to other pipelines and linear infrastructure projects, CO2 pipelines are subject to several layers of regulations at the local, state and federal levels:

Safety

The Pipelines and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), a federal agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation, regulates the safety of U.S. pipeline infrastructure and provides national standards for the safe and responsible design, construction, maintenance and operation of pipelines. In some cases, a state may assume regulatory authority over the safety of intrastate CO2 pipelines if it adopts rules that are as stringent as, or more stringent than, PHMSA’s minimum standards.

Environment, Water and Land

CO2 pipelines are subject to strict state and federal regulations that seek to protect water sources, agricultural land, the local environment and wildlife. These include the Clean Water Act, National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), Endangered Species Act and more. Local and tribal communities are also engaged throughout these permitting processes.

Siting and Construction

Before building a CO2 pipeline, an operator must receive regulatory approval for the location and construction of the project. Unlike interstate natural gas pipelines, which are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), there is currently no option to site an interstate CO2 pipeline solely using a federal process. The siting and construction of both interstate and intrastate CO2 pipelines are largely regulated at the local and state levels, creating a patchwork of regulatory approaches and standards across the country.

When siting and constructing a CO2 pipeline, each developer is subject to the unique eminent domain laws of each state, and many states lack clear eminent domain policies for these pipelines. Eminent domain, a last resort option for building major infrastructure projects, is a process by which the government can permit a company to use private property without the express permission of the landowner. This can only occur if the government determines that a property owner is fairly compensated and the project benefits the public. Eminent domain has been used to build roads, develop water supplies, construct pipelines and more. This process isn’t new, but it is rare. In fact, between 2008 and 2018, less than 2 percent of easements for interstate natural gas pipelines involved eminent domain.

Rate Regulation

Rate regulation refers to a process by which an authority can regulate the price pipeline operators can charge for transporting a material (e.g., natural gas, oil). Unlike interstate natural gas and oil pipelines, there is no federal ratemaking authority for carbon pipelines. Today, the majority of carbon pipelines are private access and do not require rate regulation. However, this is poised to change as the carbon pipeline network grows and more entities require access to carbon transportation via common carrier or open-access pipelines.

Regulatory Landscape for Carbon Dioxide Pipelines

*PHMSA regulates interstate CO2 pipelines. PHMSA also regulates intrastate CO2 pipelines if a state does not have a certified safety program. If a state has a certified safety program, the state can only regulate intrastate pipelines, not interstate.

**CO2 pipelines are subject to various regulatory requirements pertaining to the environment, water, and wildlife under federal legislation such as the National Environmental Protection Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and more. Different federal agencies may have jurisdiction over permits and assessments required under these laws, such as the Army Corps of Engineers, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of Energy and more.

CO2 pipelines have a strong safety record. Over the last 20 years, zero fatalities have resulted from the few pipeline incidents that have occurred. CO2 is stable, non-flammable, and non-combustible. In fact, CO2 is used in fire extinguishers to put out flames. We also breathe CO2 in and out every day.

On the ground, pipeline operators take measures to ensure the safety and integrity of pipeline infrastructure. In addition to monitoring the integrity of the pipelines and conducting regular maintenance, operators mitigate corrosion by limiting the amount of water and other contaminants that enter a CO2 pipeline. For example, before CO2 enters a carbon capture system, contaminants must be removed, and before being placed into a pipeline, the CO2 is dehydrated to reduce the presence of water.

A leak is the unintentional release of a substance or material from a pipeline. The overall CO2 leaked from pipelines is limited – approximately 0.001 – 0.005% of the total volume of CO2 that is transported through pipelines annually. To mitigate leaks, PHMSA requires new and refurbished CO2 pipelines to utilize remotely controlled or automatic shut-off valves, thus reducing safety risks and allowing first responders to act swiftly.

Operators regularly implement procedures to prevent and mitigate the impact of incidents, and PHMSA requires operators to communicate safety-related information with the public. CO2 pipelines are a vital part of American infrastructure, and operators are committed to working with PHMSA and other regulatory authorities to ensure robust safety standards for all pipelines.

CO2 pipelines benefit the public by boosting local economies, providing direct financial benefits for landowners, strengthening energy and national security and helping to lower carbon emissions:

Establish Efficient Permitting Processes — A decentralized regulatory structure for siting interstate carbon pipelines has led to significant uncertainty for project developers who require access to pipeline infrastructure. An unpredictable regulatory environment can result in delays, increased project costs, and, in some cases, the cancellation of projects altogether. These challenges underscore the need for a more predictable, transparent and cohesive regulatory framework to support the safe and efficient deployment of interstate carbon pipeline infrastructure. The federal government – with agencies such as FERC – can play a critical role in supporting the coordinated and effective siting and permitting of carbon pipelines. Congress could consider establishing an optional federal siting pathway for interstate CO2 pipelines, allowing project developers the flexibility to choose a federal permitting process.

Expand Research, Development and Deployment (RD&D) – Dedicated RD&D is critical to building out CO2 pipelines at the scale that is needed and enabling the commercialization of advanced materials and technologies for this infrastructure. Pipeline RD&D should focus on, among other areas, enhanced geohazard monitoring, advanced leak detection and monitoring, advanced pipeline materials and integrity, retrofitting natural gas pipelines for CO2 transport and more. Increased coordination between the Department of Energy (DOE) and other federal agencies, such as PHMSA, the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) and FERC will also be key to expanding critical RD&D efforts for CO2 pipeline infrastructure.

A key opportunity for Congress is to reintroduce and advance the bipartisan Next Generation Pipelines Research and Development Act, which passed the House of Representatives during the 118th Congress. This legislation would modernize our pipeline system by authorizing the U.S. Department of Energy’s research and development programs focused on various pipeline technologies and uses, including the transportation of carbon dioxide.

Reauthorize PHMSA – PHMSA’s three-year authorization in the bipartisan PIPES Act of 2020 expired in September 2023. Reauthorizing and providing updated funding profiles for PHMSA’s activities and programs are critical for ensuring a safe and reliable pipeline network across the United States. During the 118th Congress, PHMSA reauthorization legislation, the PIPES Act of 2023, led by Chairman Sam Graves (R-MO), passed the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure with strong bipartisan support. This Congress, policymakers could reintroduce this legislation, which would mandate that the agency finalize updated CO2 pipeline safety rules.

By building CO2 pipeline infrastructure, we are not only building our capacity to reduce emissions and protect our environment, we’re also creating jobs, bolstering local economies and continuing to use the energy sources that make our country strong. In America, we’re not afraid to build — it’s what we do.