Examining Policies to Counter China

U.S. House Committee on Financial Services

Below is my testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services on February 25, 2025 in a hearing titled, “Examining Policies to Counter China”

Watch Niko’s Opening Remarks

Read Niko’s Full Testimony as Seen Below

Good morning Chairman Hill, Ranking Member Waters, and Members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to address the Committee today on the imperative of American energy dominance around the world to ensure our national security at home and leadership abroad.

My name is Nicholas McMurray. I am the Managing Director of International and Nuclear Policy at ClearPath, a 501(c)(3) organization that works to accelerate American innovation to reduce global energy emissions. Industry-informed but philanthropically funded, ClearPath runs like a business — we seek out the top private sector innovators, determine the barriers to their success, and help cultivate the environment that allows them to scale up.

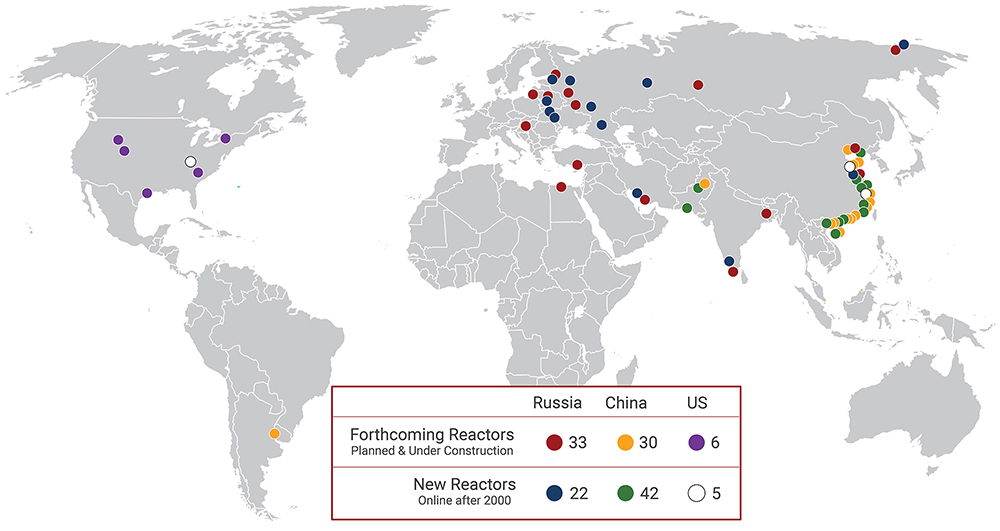

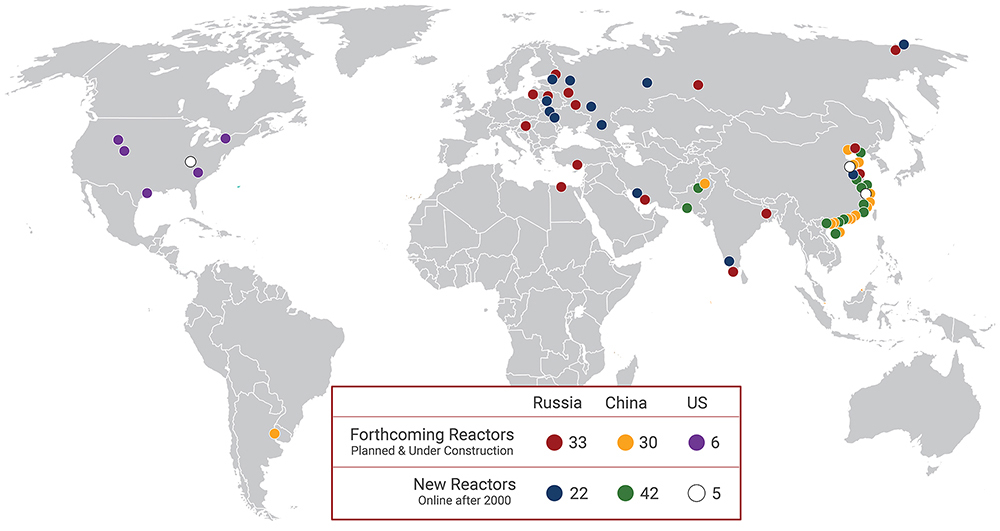

The global energy landscape is rapidly evolving, shaped by growing demand, shifting supply chains, and heightened competition among major energy producers. For example, China currently has 57 nuclear reactors in operation and 28 reactors under construction. In contrast, while the U.S. has 94 reactors in operation, it currently does not have any commercial reactors under construction although several of the advanced reactor demonstrations supported by public-private partnerships are close. China also continues to finance and construct large-scale energy infrastructure in nations like Pakistan and Argentina. Nations around the world are seeking more reliable, affordable, and cleaner energy solutions to fuel their economies while breaking dependencies on predatory suppliers like China. This presents a significant opportunity for American energy dominance as U.S. companies lead in innovation across nuclear, natural gas, and other cutting-edge energy technologies. Strategic financing tools and pro-growth policies can help the U.S. strengthen its energy leadership, open new markets and counter adversaries.

The Global Energy Landscape

The world’s energy consumption is at an all-time high. Some estimates show the demand for electricity generation in the U.S. will double by 2050. Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) notes that global energy demand is accelerating its growth rate.

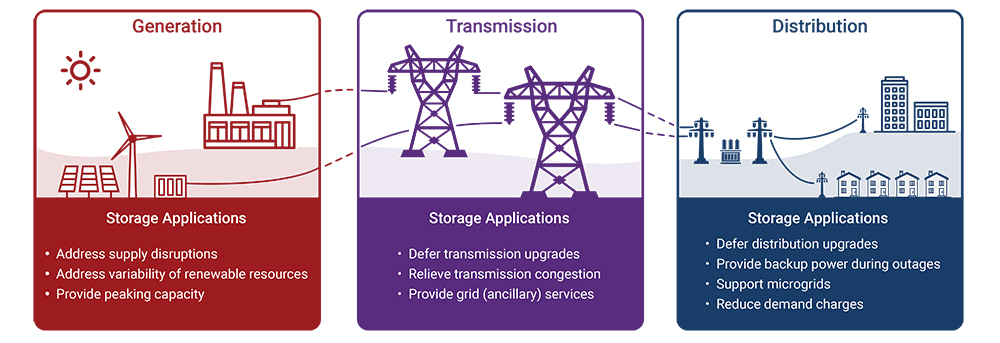

American private sector innovation is the key to meeting today’s rising energy demand while ensuring that the U.S. remains the global leader in clean, reliable, and affordable energy solutions. By rapidly scaling the deployment of cutting-edge energy technologies – such as advanced nuclear, clean hydrogen, long-duration storage, and carbon management – the U.S. can drive down costs and establish itself as the premier exporter of these solutions.

This kind of commitment to innovation extends beyond domestic borders. The U.S. has demonstrated its ability to address international energy challenges. For decades, the European Union (EU) relied heavily on Russian natural gas imports, which grew in share even after the invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014. In one year, the U.S. surged its Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exports, driving Russia’s market share in the EU down from 40 percent in 2021 to 8 percent in 2023. The economic opportunity for America’s clean energy innovators is immense, with some estimates suggesting a potential $10 trillion in domestic market and export opportunities reaching $330 billion annually by 2050. More importantly, widespread adoption of these American technologies can strengthen U.S. economic and geopolitical influence while significantly reducing global emissions.

Meeting these historic energy needs at home and abroad demands a strategic approach. While the U.S. remains a leader in key areas like nuclear power operations and energy innovation, America’s competitors are rapidly scaling up their domestic and international investments. China and Russia aggressively expand their influence in global energy markets by financing and constructing large-scale projects, extending their geopolitical reach. Their strategies include nuclear, oil and gas infrastructure, renewable projects, critical minerals, and others that entrench reliance on their state-backed enterprises. For example, in 2024, China started construction on about 94.5 GW of coal capacity, which is just shy of total U.S. nuclear energy capacity. In addition, China also invested $940 billion in clean energy last year. Without a concerted effort to expand American energy production at home and exports abroad, U.S. companies risk being sidelined in rapidly expanding global markets.

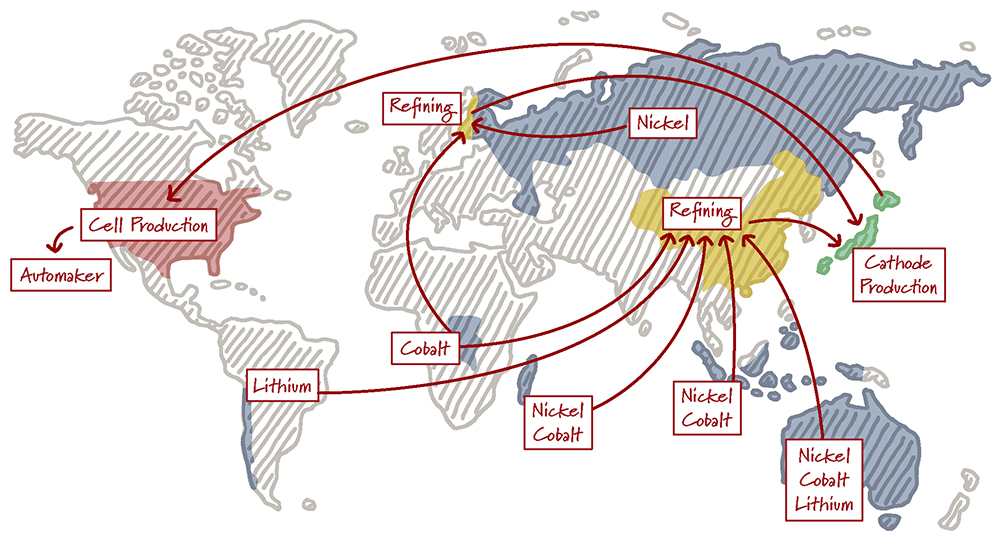

The past few years have exposed vulnerabilities in global energy markets, underscoring the need for reliable, market-driven alternatives. Supply chain disruptions from COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s tightening grip on clean energy supply chains have forced many countries to reassess their energy partnerships. Some nations, such as Finland, have already backed away from Russian projects, and others, from the Philippines to Panama, are seeking alternatives to avoid excessive debt burdens associated with Chinese financing.

China and others have leveraged their financial institutions to provide generous, long-term financing to developing countries, securing energy deals that come with diplomatic strings attached. Russia, for example, has funded a majority of Egypt’s and Bangladesh’s nuclear projects. By offering full-service packages – including financing, construction, and long-term operational support – China and Russia are creating decades-long dependencies on their technologies and fuel supplies. This strategy not only strengthens their economic and political influence but also undermines energy security in regions critical to U.S. interests.

The U.S. can contend by providing competitive financing and export support for diverse energy technologies, ensuring nations seeking long-term energy solutions turn to America over global competitors. U.S. innovators are already leading in these technologies, and while federal support exists, it needs modernization to stay competitive. With the right focus, America can seize this moment.

Leveling the Playing Field for U.S. Energy Dominance

U.S. government export and development financing plays a pivotal role in advancing America’s strategy for global energy dominance. By providing financial support to expand innovative American energy technologies abroad, agencies like the Export-Import Bank (EXIM) and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) can help solidify U.S. leadership in international energy markets. Working alongside interagency partners at the Departments of Energy, State, Commerce, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) and others to level the playing field for America’s private sector leaders both strengthens U.S. energy security and promotes the adoption of innovative American solutions worldwide.

The U.S. government will not – and should not – attempt to match China dollar-for-yuan in state-backed subsidies. Instead, America must take a more agile and strategic approach, using targeted financing tools to de-risk projects, attract private capital, and create market conditions that empower U.S. innovators and manufacturers to compete and lead globally without relying on government subsidies to prop them up.

Trade and development finance prioritizes investment in infrastructure, manufacturing, energy security, and economic partnerships that benefit both the U.S. and its trading partners. EXIM and DFC provide loans and guarantees that must be repaid, ensuring taxpayer dollars are used efficiently while expanding opportunities for U.S. businesses. This approach creates American jobs, strengthens economic ties, and positions the U.S. as the preferred energy partner for nations seeking reliable, long-term energy solutions.

An interagency effort in 2019 exemplifies the influence that the U.S. has in leveraging its financing agencies to compete with China and advance international American energy dominance. To counter China’s growing influence in Romania’s nuclear sector, the U.S. launched a multi-pronged strategy, including a Department of Energy (DOE) Intergovernmental Agreement and an EXIM Memorandum of Understanding, signaling long–term U.S. commitment. This diplomatic push resulted in the cancellation of China’s negotiations to build Units 3 and 4 of the Cernavoda nuclear plant in Romania – an estimated $7.4 billion project. In 2023, EXIM approved a $57 million loan for pre-construction studies at Cernavoda by Fluor Enterprises, supporting 200 American jobs. Further, EXIM signed a letter of interest for $3 billion towards the deployment of the project, set to be operational by 2031.

In addition to the Cernavoda example, the U.S. is continuing to expand its nuclear financing activity in Eastern Europe. EXIM and DFC expressed letters of interest for multiple projects, including the NuScale small modular reactor (SMR) deployment in Romania, the GE-Hitachi SMRs in Poland as well as the Westinghouse AP1000 nuclear plants in Poland.

Beyond nuclear energy, EXIM and DFC are proven valuable tools for exporting American technology abroad. In late 2024, EXIM approved a loan for over $500 million to support a natural gas project in Guyana, which will double the nation’s installed electricity capacity, drive an annual emissions reduction of over 460,000 tons of carbon dioxide and generate 1,500 American jobs. In the same year, DFC committed $126 million to a 31 MW geothermal plant in Indonesia with the U.S.-based Ormat Technologies as a part owner and developer. Additionally, both agencies are working to diversify and secure critical minerals supply chains, reducing reliance on China.

These efforts highlight the strategic value of sustained U.S. financial engagement in building energy partnerships, advancing U.S. clean energy technologies and countering adversarial influence across the globe. And these aren’t handouts, they are commercially oriented efforts that earn a return on investment – $80 million back to taxpayers in 2024.

Sharpening America’s Toolkit

Both the EXIM Bank and DFC are due for reauthorization this Congress, creating a prime opportunity to sharpen and enhance America’s foreign policy toolkit to benefit U.S. national, economic, and energy security. Other countries are bringing enormous resources to bear in an effort to dominate global energy markets, which requires the U.S. to be more agile and strategic in order to advance its long-term goals.

As America’s official export credit agency (ECA), EXIM is one of the best tools for increasing export competitiveness. An increasingly competitive trade finance landscape has transformed ECAs worldwide from lenders of last resort into proactive partners, building capacity and creating business opportunities for their domestic exporters. This shift is largely aimed at countering China’s non-market tactics, designed to eliminate competition in strategic markets and control geostrategic supply chains such as clean energy. China offers financing at favorable terms and conditions non-compliant with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Arrangement on Export Credit and Trade Related Support, which binds nations like the U.S. to acceptable terms for global trade. While China’s practices are a primary concern, other countries have already begun adapting their ECA policies to promote domestic industries, underscoring the potential for EXIM to set the pace in modernizing trade finance and reassert American global leadership.

While EXIM has made strides in the energy sector, its current capabilities limit the Bank from achieving energy dominance. Not only is China offering significantly higher levels of overall export credit than the U.S., but it is also shifting from its use of export credit to financing from state-owned commercial banks. This poses an issue as these forms of financing are often more covert and difficult for the U.S. to track and compete against. Strategically tailored reforms can position the U.S. to advance national interests by improving its global export competition in critical sectors. The following recommendations outline key opportunities to bolster U.S. energy leadership and domestic jobs while enhancing energy security in partner countries:

- Create a National Interest Account (NIA):

EXIM’s current mandate does not account for the geostrategic value of investments, but Congress can fix this by creating a National Interest Account that prioritizes projects related to U.S. national interests. An NIA would cement EXIM’s role in the Trump Administration’s America First Trade Policy by leveling the playing field for U.S. companies against countries who already use similar tools to work against American interests and American businesses.

- Expand the China & Transformational Exports Program (CTEP):

The CTEP program, created in 2019, was a strong first step to countering Chinese influence over advanced technologies. The NIA could prioritize similar technology areas while expanding beyond a narrow focus on renewables to support a balanced strategy for clean energy technologies such as nuclear energy, carbon management, clean manufacturing and grid infrastructure to reinforce an all-of-the-above energy dominance approach.

- Default Rate Cap Exclusion for Nuclear Projects:

EXIM’s current 2% default rate cap is a unique requirement placed on the Bank that other countries do not face and discourages EXIM’s staff from meeting congressional mandates. Modifying the cap to support high capital costs technologies, like nuclear energy, would align the Bank with OECD norms and provide flexibility. This requirement, created over a decade ago and linked to an outdated lending limit, is an unnecessary obstacle.

- Reinforce the U.S. Jobs Mandate:

EXIM’s current standard to support its jobs mandate has not changed significantly since 1987 and is internal policy rather than Congressionally directed. In a memo to the Board, EXIM reported that its current standard was the largest obstacle to the Bank’s competitiveness and that it was the least flexible policy among all ECAs globally. To account for globalized supply chains, Congress could authorize a forward-looking metric to modernize EXIM’s mission to support U.S. jobs through exports. This incentivizes companies with globalized supply chains to shift to U.S. exporters in strategic industries.

- Bolster Domestic Manufacturing:

EXIM’s Make More In America Initiative (MMIA) finances export-oriented U.S. manufacturers. This unique financing tool builds manufacturing capacity while working to improve America’s trade position. With a clear tie to national interests, reauthorization could codify and strengthen the MMIA by including it in the NIA. Building domestic industrial strength in strategic areas like critical minerals could allow U.S. clean energy manufacturers to establish a leadership stake in securing supply chains.

- Modernize the Mission:

EXIM could update its mission to support American jobs and advance U.S. national interests. EXIM’s U.S. jobs mandate remains critically important and could be reinforced with the recommendation above. However, an additional provision to consider national interests could strengthen the Bank’s direction to proactively develop a project pipeline aligned with U.S. national security objectives, fostering a clear understanding that global competitiveness is a core priority.

EXIM’s 2026 reauthorization is a crucial opportunity to strengthen the Bank’s ability to compete and advance American national interests. However, in the short term, Congress can work with the Administration to confirm at least two additional board members to restore the Bank’s quorum. Without a board quorum, EXIM cannot approve transactions over $25 million, hindering its ability to support American businesses competing in the global marketplace. The consequences of a non-functioning EXIM are significant, particularly when we consider the economic opportunities and job growth potential lost between 2015 and 2019 when the Board last lacked a quorum. During the three full fiscal years (FY 2016-2018) when EXIM lacked a quorum, it supported only 125,000 U.S. jobs and $22 billion in U.S. export sales. In contrast, during the three prior fiscal years when EXIM was fully operational, it supported 624,000 U.S. jobs and $115 billion in U.S. export sales. This highlights the stark difference a fully functioning EXIM can make for American businesses and workers.

It is crucial that the Bank signals its long-term reliability and commitment to supporting American businesses, especially as it looks ahead to its 2026 reauthorization. A fully operational EXIM is not just good for business; it’s good for America. It supports American jobs, strengthens our manufacturing base, and enhances our competitiveness in the global economy. It is important the President and Senate prioritize filling the vacant EXIM Board seats and restoring its quorum without delay.

Finally, the DFC – created during the first Trump Administration – already established itself as a key player in the United States’ national interests for global energy leadership and in countering China. The DFC has already made notable geostrategic clean energy investments and in 2020, removed its moratorium on funding nuclear energy projects. Through DFC’s reauthorization this year, Congress has the opportunity to make targeted, critical improvements to further enhance DFC’s capabilities and efficiency, including 1) fixing the current budgetary scoring system DFC’s equity stakes; 2) increasing the DFC’s lending authority to provide the financial flexibility needed to engage in large-scale energy infrastructure projects; 3) and broadening the DFC’s country eligibility criteria to invest in more strategically significant countries and regions, aligning with U.S. foreign policy objectives.

Aligning International Financial Institutions with U.S. Foreign Policy

International Financial Institutions (IFIs) like the World Bank also have a critical role to play in advancing firm, clean, and affordable energy infrastructure worldwide. Yet, they have been slow to align their financing with both energy security and geopolitical realities. These institutions were originally designed to support economic development and stability, but their outdated policies – including self-imposed restrictions on financing nuclear power and other firm energy sources – have left a gap that China has eagerly exploited. Over the past decade, China has dominated energy project financing, investing more than all major Western-backed development banks combined.

Without reform, IFIs risk becoming passive enablers of China’s broader geopolitical strategy to make developing countries dependent on Chinese technology and supply chains. To prevent this, the U.S. should push for reforms at IFIs not only to lift restrictions on nuclear energy financing but also to pursue broader procurement reforms that are essential to ensuring U.S. companies – not just Chinese state-backed firms – can compete fairly for IFI-backed energy projects. The United States, as a leading shareholder in these institutions, has the influence to drive these reforms. A more assertive U.S. approach would not only counter China’s intentions but also ensure that developing nations have access to a wider range of market-driven, secure, and clean energy solutions that align with American national security interests.

Additionally, the Chinese Communist Party continues to benefit from developing nation status at the World Bank, amongst other international institutions, despite running the world’s second-largest economy. Due to this status, China continues to receive over one billion in World Bank financing each year, which would be better used to contribute to economically developing democracies.

Another near-term step that Congress and the Administration can take is to establish a Nuclear Energy Trust Fund at the World Bank. The World Bank is one of the largest funders of energy infrastructure in the developing world, with an active portfolio of roughly $40 billion active projects in energy and extractives. The Bank is also an advisor to developing countries working to select partners and technologies. Despite this, the World Bank has no nuclear energy expertise and, by internal policy, refuses to build internal capacity. Russia and China have filled this role by exporting reactors with exploitive state-backed financing. Trust Funds are managed by the World Bank on behalf of funding partners, and complement core activities of the Bank. A Nuclear Energy Trust Fund would build analytical capacity to assess the viability of nuclear projects in Bank shareholder countries, giving the Bank expertise it could tap into when requested.

The global demand for nuclear energy is intensifying as countries aim to meet rising energy needs while curbing emissions. Over 30 countries have committed to tripling nuclear power. Relatedly, 14 major banks support this goal. To meet this interest, the World Bank needs to modernize its stance on nuclear energy, starting with building internal expertise that will allow the Bank to provide advisory services and assess nuclear projects. A trust fund could be the first step toward the Bank supporting nuclear energy, opening a major new financing source for U.S. companies looking to export, and providing objective expertise to buyer countries as they evaluate technology options.

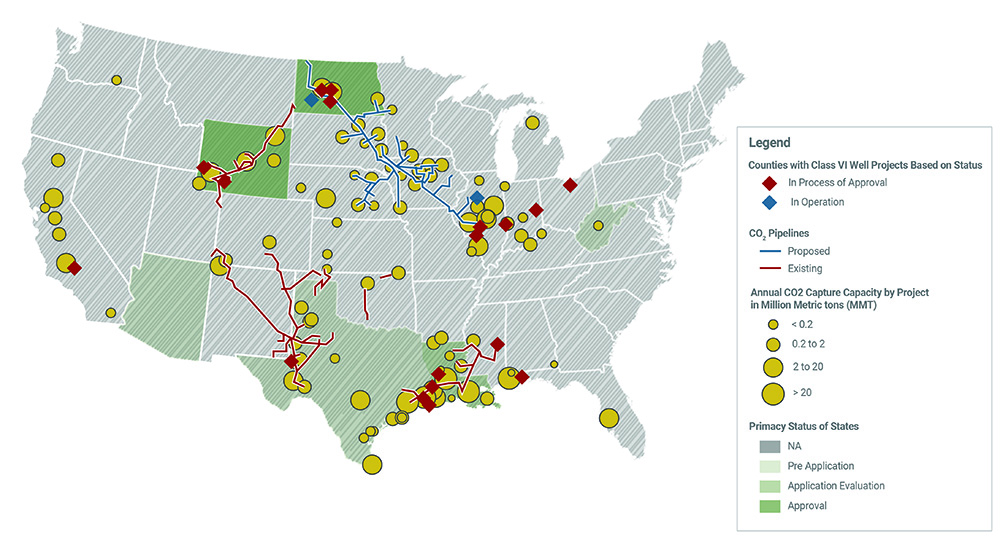

American Innovation Will Power the Administration’s Goals

The Trump Administration has a bold vision for a reindustrialized America that leads the world in everything from manufacturing to AI. As energy-intensive industries grow, so too will the demand for power — a trend already evident nationwide. To meet this ambitious agenda, the nation must prioritize developing abundant, reliable, and affordable energy. This means building on longstanding leadership in traditional energy sources like natural gas, while also expanding into new energy technologies. American expertise in oil & gas sectors can be leveraged to capitalize on burgeoning opportunities in LNG, geothermal, and carbon capture, driving significant economic gains. The U.S. will also need to build out supply chains to match this ambition, ensuring that whatever next-generation technologies succeed, whether nuclear fission, fusion, geothermal, long-duration batteries, or anything else, that they will be made here in America.

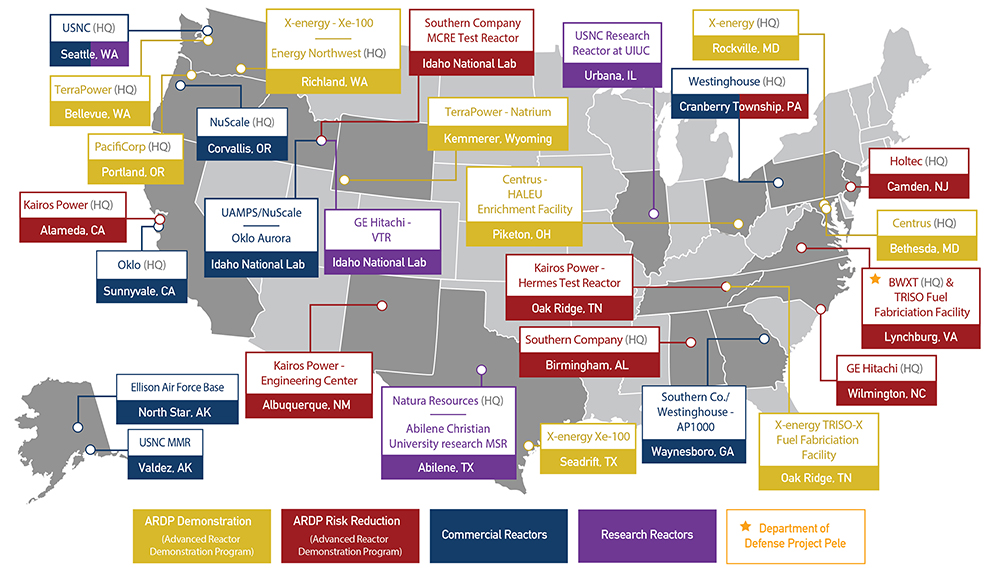

America’s greatest asset is its unmatched capacity to innovate. The U.S. is home to a vibrant private industry aiming to demonstrate market-competitive advanced technologies. Tech companies like Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta signaled this commitment through major nuclear energy investments, complemented by groundbreaking geothermal technologies from companies like Sage Geosystems and Fervo Energy. Furthermore, Form Energy’s iron-air battery project in Maine is set to deliver the highest energy capacity of any battery system in the world.

At ClearPath, we believe in markets over mandates. But in order to achieve energy dominance, the government must provide a predictable environment for developers — one where long-term, stable policy frameworks help unlock private investment. Congress has made significant efforts to modernize permitting at Agencies like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and at a broader scale through changes to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. These efforts should increase investor confidence by creating clear and consistent pathways to market.

Additionally, the government has provided support to the private sector through targeted tax credits and demonstration programs like those created by the first Trump Administration under the Energy Act of 2020. These programs provide financial stability and encourage the scaling of new technologies like nuclear, carbon capture, geothermal, and more that can deliver reliability, affordability, and substantial emissions reductions. Maintaining an all of the above approach to supporting new technologies is necessary to ensure American energy dominance, which is fundamental to our national security but also to the Administration’s goal of reindustrializing American industry. The work of this Committee will be critical to providing certainty and predictability for companies seeking to raise capital and compete on a global stage.

Conclusion

The scale and urgency of building new energy infrastructure to meet America’s growing demand and strengthen our energy leadership globally requires bold action. The U.S. must focus on making these technologies here and selling them abroad. Ensuring American leadership in energy means having financial tools that are properly designed for U.S. companies to compete with aggressive state-backed financing from China and Russia.

Congress has a unique opportunity to strengthen American solutions by advancing commonsense policies, including modernizing development and export financing to support nuclear, LNG, and other critical energy technologies that align with our strategic national interests. By advancing smart reforms, the U.S. can unlock private-sector investment, reduce reliance on adversarial nations, and reinforce its role as the world’s energy leader.

ClearPath looks forward to working with this Committee to advance these priorities, and I look forward to today’s discussion.